Keith Richards

Keith Richards | |

|---|---|

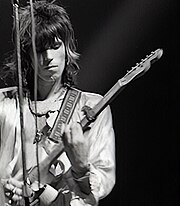

Richards in 2022 | |

| Born | 18 December 1943 |

| Other names | Keith Richard |

| Education | Dartford Technical School Sidcup Art College |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Spouse | |

| Partner | Anita Pallenberg (1967–1980) |

| Children | 5, including Theodora and Alexandra |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Member of | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | keithrichards |

Keith Richards[nb 1] (born 18 December 1943) is an English musician, songwriter, singer and record producer who is an original member, guitarist, secondary vocalist, and co-principal songwriter of the Rolling Stones. His songwriting partnership with the band's lead vocalist Mick Jagger is one of the most successful in history. His career spans over six decades, and his guitar playing style has been a trademark of the Rolling Stones throughout the band's career. Richards gained press notoriety for his romantic involvements and illicit drug use, and he was often portrayed as a countercultural figure. First professionally known as Keith Richard, by the early 1970s he had fully asserted his family name.

Richards was born in and grew up in Dartford, Kent. He studied at the Dartford Technical School and Sidcup Art College. After graduating, Richards befriended Jagger, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, Ian Stewart and Brian Jones and joined the Rolling Stones. As a member of the Rolling Stones, Richards also sings lead on some Stones songs. Richards typically sings lead on at least one song a concert, including "Happy", "Before They Make Me Run", and "Connection". Outside of his career with the Rolling Stones, Richards has also played with his own side-project, The X-Pensive Winos. He also appeared in two Pirates of the Caribbean films as Captain Teague, father of Jack Sparrow, whose look and characterisation was inspired by Richards himself.

In 1989, Richards was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and in 2004 into the UK Music Hall of Fame with the Rolling Stones. Rolling Stone magazine ranked him fourth on its list of 100 best guitarists in 2011. In 2023, Rolling Stone's ranking was 15th.[5] The magazine lists fourteen songs that Richards wrote with Jagger on its "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" list.

Early life

Richards was born on 18 December 1943 at Livingston Hospital, in Dartford, Kent, England.[6] He is the only child of Doris Maud Lydia (née Dupree) and Herbert William Richards. His father was a factory worker who was wounded in the Second World War during the Normandy invasion.[7] Richards's paternal grandparents, Ernie and Eliza Richards, were socialists and civic leaders, whom he credited as "more or less creat[ing] the Walthamstow Labour Party", and both were mayors of the Municipal Borough of Walthamstow in Essex, with Eliza becoming mayor in 1941.[8][9] His great-grandfather's family originated from Wales.[7][10][11]

His maternal grandfather, Augustus Theodore "Gus" Dupree, who toured Britain with a jazz big band, Gus Dupree and His Boys, fostered Richards's interest in the guitar.[12] Richards has said that it was Dupree who gave him his first guitar.[13] His grandfather 'teased' the young Richards with a guitar that was on a shelf that Richards couldn't reach at the time. Finally, Dupree told Richards that if Richards could reach the guitar, he could have it.[14] Richards then devised all manner of ways of reaching the guitar, including putting books and cushions on a chair, until finally getting hold of the instrument, after which his grandfather taught him the rudiments of Richards's first tune, "Malagueña".[14] He worked on the number 'like mad', and then his grandfather let him keep the guitar, which he called 'the prize of the century'. Richards played at home, listening to recordings by Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and others.[15] His father, on the other hand, disparaged his son's musical enthusiasm.[16] One of Richards's first guitar heroes was Elvis's guitarist Scotty Moore.[17]

Richards attended Wentworth Primary School with Mick Jagger[18] and was his neighbour until 1954 when the Richards and Jagger families both moved.[19] From 1955 to 1959, Richards attended Dartford Technical High School for Boys. He never sat the eleven-plus due to illness.[20][21][22] Recruited by Dartford Tech's choirmaster, R. W. "Jake" Clare, he sang in a trio of boy sopranos at, among other occasions, Westminster Abbey for Queen Elizabeth II.[23] In 1959, Richards was expelled from Dartford Tech for truancy and transferred to Sidcup Art College,[24][25] where he met Dick Taylor.[26][27] At Sidcup, he was diverted from his studies proper and devoted more time to playing guitar with other students in the boys' room. At this point, Richards had learned most of Chuck Berry's solos.[28]

Richards met Jagger again by chance on a train platform when Jagger was heading for classes at the London School of Economics.[29] The mail-order rhythm and blues albums from Chess Records by Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters that Jagger was carrying revealed a mutual interest[30][31] and led to a renewal of their friendship. Along with mutual friend Dick Taylor, Jagger was singing in an amateur band, Little Boy Blue and the Blue Boys, which Richards soon joined.[32][33] The Blue Boys folded when Brian Jones, after sharing thoughts on their joint interest in the blues music, invited Mick and Keith to the Bricklayers Arms pub, where they then met Ian Stewart.[34][35]

By mid-1962, Richards had left Sidcup Art College[36] to devote himself to music, and moved into a London flat with Jagger and Jones. His parents divorced at about the same time, resulting in his staying close to his mother and remaining estranged from his father until 1982.[37]

After the Rolling Stones signed to Decca Records in 1963, the band's manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, dropped the s from Richards's surname, believing that Keith Richard, in his words, "looked more pop",[38] and that it would echo the name of the British rock and roll singer Cliff Richard.[39] During the late 1970s, Richards re-established the s in his surname.[40]

Musicianship

Richards plays both lead and rhythm guitar parts, often in the same song; the Stones are generally known for their guitar interplay of rhythm and lead ("weaving") between him and the other guitarist in the band – Brian Jones (1962–1969), Mick Taylor (1969–1975), or Ronnie Wood (1975–present). In the recording studio Richards sometimes plays all of the guitar parts, notably on the songs "Paint It Black", "Ruby Tuesday", "Sympathy for the Devil", and "Gimme Shelter". He is also a vocalist, singing backing vocals on many Rolling Stones songs as well as occasional lead vocals, such as on the Rolling Stones' 1972 single "Happy", as well as with his side project, the X-Pensive Winos.

Bandleader

Since the mid-1960s, Richards and Mick Jagger have been the primary songwriters for the Stones, as well as the band's primary producers since the mid-1970s (credited as the Glimmer Twins), often in collaboration with an outside producer. Former keyboardist Ian Stewart once said that Richards was the Rolling Stones' bandleader; Richards has said that his job is merely "oiling the machinery". Unlike many bands where the drummer sets the pace and acts as a timesetter for a song, Richards fills that role for the Rolling Stones. Both former bassist Bill Wyman and current guitarist Ronnie Wood have said that the Stones did not follow the band's long-time drummer, Charlie Watts, but rather followed Richards, as there was "no way of 'not' following" him.[41][42]

Guitarist

Chris Spedding calls Richards's guitar playing "direct, incisive and unpretentious".[43] Richards says he focuses on chords and rhythms, avoiding flamboyant and competitive virtuosity and trying not to be the "fastest gun in the west".[41] Richards prefers teaming with at least one other guitarist and has almost never toured without one.[44] Chuck Berry has been an inspiration for Richards,[45] and, with Jagger, he introduced Berry's songs to the Rolling Stones' early repertoire. In the late 1960s Brian Jones's declining contributions led Richards to record all guitar parts on many tracks, including slide guitar. Jones's replacement, Mick Taylor, played guitar with the Rolling Stones from 1969 to 1974. Taylor's virtuosity on lead guitar led to a pronounced separation between lead and rhythm guitar roles, most notably onstage.[41] In 1975 Taylor was replaced by Wood, whose arrival marked a return to a guitar interplay Richards called "the ancient art of weaving", which he and Jones had gleaned from Chicago blues.[46]

A break in touring during 1967–1968 allowed Richards to experiment with open tunings. He mainly used open tunings for fingered chording, developing a distinctive style of syncopated and ringing I–IV chording heard on "Street Fighting Man" and "Start Me Up".[47] Richards's favoured – but not exclusively used – open tuning is a five-string open G tuning: GDGBD. Richards often removes the lowest string from his guitar, playing with only five strings and letting the band's bass player pick up those notes, as the lower string just "gets in the way" of Richards's playing.[48] Several of his Telecasters are tuned this way. This tuning is prominent on Rolling Stones recordings, including "Honky Tonk Women", "Brown Sugar", and "Start Me Up".[49] Richards has stated that banjo tuning was the inspiration for this tuning.[50]

Richards regards acoustic guitar as the basis for his playing,[51] believing that the limitations of electric guitar would cause him to "lose that touch" if he stopped playing an acoustic.[49] Richards plays acoustic guitar on many Rolling Stones tracks, including "Play with Fire", "Brown Sugar", and "Angie". All guitars on the studio versions of "Street Fighting Man" and "Jumpin' Jack Flash" feature acoustic guitars overloaded to a cassette recorder, then re-amped through a loudspeaker in the studio.[52]

Vocals

Richards sang in a school choir – most notably for Queen Elizabeth II – until adolescence's effect on his voice forced him out of it.[53] He has sung backing vocals on every Rolling Stones album. Since Between the Buttons (1967), he has sung lead or co-lead on at least one track (see list below) of every Rolling Stones studio album except Their Satanic Majesties Request, Sticky Fingers, It's Only Rock 'n Roll, and Blue & Lonesome.

He has sung lead on more than ten Rolling Stones songs, including "Happy", "You Got the Silver", and "Connection".[54] During the Rolling Stones' 1972 tour, the Richards-sung "Happy" entered into their concert repertoire, and since then he has sung lead vocals on one or two songs each concert[55][56][57] in order to give Jagger time to change his outfit.[56] Keith usually starts with Max Miller routines such as "It's nice to be here – it's nice to be anywhere", in order to give the audience a moment to catch its proverbial breath.[56] During the 2006 and 2007 Rolling Stones' tours, Richards sang "You Got the Silver" (1969) without playing any instrument.[58]

Songwriting

Richards and Jagger began writing songs together in 1963, prompted by manager Andrew Loog Oldham, who believed the band could not depend on outside songwriters.[59] The earliest Jagger/Richards collaborations were recorded by other artists, including Gene Pitney, whose rendition of "That Girl Belongs to Yesterday" was their first top-ten single in the UK.[60] They scored another top-ten hit in 1964 with the debut single written for Marianne Faithfull, "As Tears Go By".

The first top-ten hit for the Rolling Stones with a Jagger and Richards original was "The Last Time" in early 1965;[61] "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" (also 1965) was their first international number-one recording. Richards has stated that the "Satisfaction" riff came to him in his sleep; he woke up just long enough to record it on a cassette player by his bed.[62] Since Aftermath (1966) most Rolling Stones albums have consisted mainly of Jagger and Richards originals. Their songs reflect the influence of blues, R&B, rock and roll, pop, soul, gospel, and country, as well as forays into psychedelia and Dylanesque social commentary. Their work in the 1970s and beyond has incorporated elements of funk, disco, reggae, and punk.[63] Richards has also written and recorded slow torchy ballads, such as "You Got the Silver" (1969), "Coming Down Again" (1973), "All About You" (1980) and "Slipping Away" (1989). His songwriting partnership with Mick Jagger is one of the most successful in history.[64][65]

In his solo career, Richards has often shared co-writing credits with drummer and co-producer Steve Jordan. Richards has stated, "I've always thought songs written by two people are better than those written by one. You get another angle on it."[63]

Richards has frequently expressed that he feels less like a creator than a conduit when writing songs: "I don't have that God aspect about it. I prefer to think of myself as an antenna. There's only one song, and Adam and Eve wrote it; the rest is a variation on a theme."[63] Richards was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1993.[66]

Record production

Richards has been active as a music producer since the 1960s. He was credited as producer and musical director on the 1966 album Today's Pop Symphony, one of manager Andrew Loog Oldham's side projects, although there are doubts about how much Richards was actually involved with it.[67] On the Rolling Stones' 1967 album Their Satanic Majesties Request, the entire band was credited as producer, but since 1974, Richards and Mick Jagger have frequently co-produced both Rolling Stones records and those by other artists under the name "the Glimmer Twins", often in collaboration with other producers.

In early 1973, Jagger and Richards developed an interest in the band Kracker, resulting in a deal whereby the band's second album was licensed for distribution outside the United States by Rolling Stones Records, making Kracker the first band on that label.[68][69][70]

Since the 1980s Richards has chalked up numerous production and co-production credits on projects with other artists including Aretha Franklin, Johnnie Johnson, and Ronnie Spector, as well as on his own albums with the X-Pensive Winos (see below). In the 1990s Richards co-produced and added guitar and vocals to a recording of nyabinghi Rastafarian chanting and drumming entitled "Wingless Angels", released on Richards's own record label, Mindless Records, in 1997.[71]

Solo recordings

Richards has released few solo recordings. His first solo single, released in 1978, was a cover of Chuck Berry's "Run Rudolph Run", backed with his version of Jimmy Cliff's "The Harder They Come". In 1987, after Jagger pursued a solo recording and touring career, Richards formed the "X-Pensive Winos" with co-songwriter and co-producer Steve Jordan, whom Richards assembled for his Chuck Berry documentary Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll.[72]

Additional members of the X-Pensive Winos included guitarist Waddy Wachtel, saxophonist Bobby Keys, keyboardist Ivan Neville, and Charley Drayton on bass. The first Winos' record, Talk Is Cheap, also featured Bernie Worrell, Bootsy Collins, and Maceo Parker. Since its release, Talk Is Cheap has gone gold and has sold consistently. Its release was followed by the first of the two US tours Richards has done as a solo artist. Live at the Hollywood Palladium, 15 December 1988 documents the first of these tours. In 1992 the Winos' second studio record, Main Offender, was released, also followed by a tour.[73] Although the Winos featured on both albums, the albums were credited to Richards as a solo artist.

A third Richards album, Crosseyed Heart, was released in September 2015.[74]

Recordings with other artists

During the 1960s, most of Richards's recordings with artists other than the Rolling Stones were sessions for Andrew Loog Oldham's Immediate Records label. Notable exceptions were when Richards, along with Mick Jagger and numerous other guests, sang on the Beatles' 1967 TV broadcast of "All You Need Is Love",[73] and when he played bass with John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Mitch Mitchell, Ivry Gitlis, and Yoko Ono as the Dirty Mac for The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus TV special filmed in 1968.[75]

In the 1970s, Richards worked outside the Rolling Stones with Ronnie Wood on several occasions, contributing guitar, piano, and vocals to Wood's first two solo albums and joining him on stage for two July 1974 concerts to promote I've Got My Own Album to Do. In December 1974 Richards also made a guest appearance at a Faces concert. During 1976 and 1977, Richards both co-produced and played on John Phillips's solo recording Pay Pack & Follow (released in 2001). In 1979 he toured the US with the New Barbarians, the band that Wood put together to promote his album Gimme Some Neck; he and Wood also contributed guitar and backing vocals to "Truly" on Ian McLagan's 1979 album Troublemaker (re-released in 2005 as Here Comes Trouble).[73]

Since the 1980s, Richards has made more frequent guest appearances. In 1981 he played on reggae singer Max Romeo's album Holding Out My Love to You. He has worked with Tom Waits on three occasions: adding guitar and backing vocals to Waits's album Rain Dogs (1985); co-writing, playing on, and sharing the lead vocal on "That Feel" on Bone Machine (1992); and adding guitar and vocals to Bad As Me (2011). In 1986 Richards produced and played on Aretha Franklin's rendition of "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and served as musical producer and band leader (or, as he phrased it, "S&M director")[76] for the Chuck Berry film Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll.[73]

In the 1990s and 2000s, Richards continued to contribute to a wide range of musical projects as a guest artist. A few of the notable sessions he has done include guitar and vocals on Johnnie Johnson's 1991 release Johnnie B. Bad, which he also co-produced; and lead vocals and guitar on "Oh Lord, Don't Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me" on the 1992 Charles Mingus tribute album Weird Nightmare. He duetted with country legend George Jones on "Say It's Not You" on the Bradley Barn Sessions (1994); a second duet from the same sessions, "Burn Your Playhouse Down", appeared on Jones's 2008 release Burn Your Playhouse Down – The Unreleased Duets. He partnered with Levon Helm on "Deuce and a Quarter" for Scotty Moore's album All the King's Men (1997). His guitar and lead vocals are featured on the Hank Williams tribute album Timeless (2001) and on veteran blues guitarist Hubert Sumlin's album About Them Shoes (2005). Richards also added guitar and vocals to Toots & the Maytals' recording of "Careless Ethiopians" for their 2004 album True Love, which won the Grammy Award for Best Reggae Album.[77] Additionally, in December 2007 Richards released a download-only Christmas single via iTunes of "Run Rudolph Run"; and the B-side was a 2003 recorded version of the famous reggae song "Pressure Drop" featuring Toots Hibbert singing with Richards backed by original Maytals band members Jackie Jackson and Paul Douglas.[73]

Rare and unreleased recordings

In 2005, the Rolling Stones released Rarities 1971–2003, which includes some rare and limited-issue recordings, but Richards has described the band's released output as the "tip of the iceberg".[78] Many of the band's unreleased songs and studio jam sessions are widely bootlegged, as are numerous Richards solo recordings, including his 1977 Toronto studio sessions, some 1981 studio sessions, and tapes made during his 1983 wedding trip to Mexico.[73]

Public image and personal life

Relationships and family

Richards was romantically involved with Italian-born actress Anita Pallenberg (d. 13 June 2017)[79] from 1967 to 1979, after which they remained cordial. Together they have a son, Marlon Leon Sundeep (named after the actor Marlon Brando), born in 1969,[80] and a daughter, Angela (originally named Dandelion), born in 1972.[81] Their third child, a son named Tara Jo Jo Gunne—after Richards's and Pallenberg's friend, Guinness heir Tara Browne, and the Chuck Berry song Jo Jo Gunne—died aged just over two months, of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), on 6 June 1976.[82] Richards was away on tour at the time, something he said has haunted him since.[83][84] He was criticised at the time for performing that night after learning of the death, but he later said it was the only way he could cope.[85] Before they became romantically linked, Pallenberg had been involved with his fellow Rolling Stones bandmate and close friend Brian Jones. The two became a couple on a trip to Morocco that Jones had to abandon when he fell ill; the subsequent relationship between Richards and Pallenberg weighed heavily on Jones, and strained his relationship with the rest of the Rolling Stones.[86]

Richards met his wife, model Patti Hansen, in 1979. They married on 18 December 1983, Richards's 40th birthday, and have two daughters, Theodora Dupree and Alexandra Nicole, born in 1985 and 1986, respectively. In September 2014 Richards published a children's book with Theodora, Gus and Me: The Story of My Granddad and My First Guitar. Theodora was reported as contributing pen and ink illustrations for the book, which was inspired by the man she was named after (Richards's grandfather Theodore Augustus Dupree).[87]

He has seven grandchildren, three from his son Marlon, two from his daughter Angela, and one each from his two younger daughters.[88][89][90]

Friendship with Mick Jagger

Richards's relationship with bandmate Mick Jagger is frequently described as "love/hate" by the media.[91][92] Richards himself said in a 1998 interview: "I think of our differences as a family squabble. If I shout and scream at him, it's because no one else has the guts to do it or else they're paid not to do it. At the same time I'd hope Mick realises that I'm a friend who is just trying to bring him into line and do what needs to be done."[93] Richards, along with Johnny Depp, tried unsuccessfully to persuade Jagger to appear in Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, alongside Depp and Richards.[94]

Richards's autobiography, Life, was published on 26 October 2010.[95] Eleven days prior to its release, the Associated Press published an article stating that in the book Richards refers to Jagger as "unbearable" and notes that their relationship has been strained "for decades".[96] His opinion softening by 2015, Richards still said Jagger could come off as a "snob" but added, "I still love him dearly ... your friends don't have to be perfect."[97]

Drug use and arrests

Music journalist Nick Kent attached to Richards Lord Byron's epithet of "mad, bad, and dangerous to know." Jagger thought that Richards's image had "contributed to him becoming a junkie".[98] In 1994, Richards said his image was "like a long shadow ... Even though that was nearly twenty years ago, you cannot convince some people that I'm not a mad drug addict."[99]

Richards's notoriety for illicit drug use stems in part from several drug busts during the late 1960s and 1970s and his candour about using heroin and other substances. Richards has been tried on drug-related charges five times: in 1967, twice in 1973, in 1977, and in 1978.[100][101] The first trial – the only one culminating in a prison sentence[101] – resulted from a February 1967 police raid on Redlands, Richards's Sussex estate, where he and some friends, including Jagger, were spending the weekend.[102] The subsequent arrest of Richards and Jagger put them on trial before the British courts, whilst also trying them in the court of public opinion. On 29 June 1967, Jagger was sentenced to three months' imprisonment for possession of four amphetamine tablets. Richards was found guilty of allowing cannabis to be smoked on his property and sentenced to one year in prison.[103] Both Jagger and Richards were imprisoned at that point: Jagger was taken to Brixton Prison in south London,[104] and Richards to Wormwood Scrubs Prison in west London.[105] Both were released on bail the next day pending appeal.[106] On 1 July, The Times ran an editorial entitled "Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?", portraying Jagger's sentence as persecution, and public sentiment against the convictions increased.[107] A month later the appeals court overturned Richards's conviction for lack of evidence, and gave Jagger a conditional discharge.[108]

On 27 February 1977, while Richards was staying in a Toronto hotel, then known as the Harbour Castle Hilton on Queen's Quay East, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police found heroin in his room and charged him with "possession of heroin for the purpose of trafficking" – an offence that at that time could result in prison sentences of seven years to life under the Narcotic Control Act.[109] His passport was confiscated, and Richards and his family remained in Toronto until 1 April, when Richards was allowed to enter the United States on a medical visa for treatment of heroin addiction.[110] The charge against him was later reduced to "simple possession of heroin".[111]

For the next two years, Richards lived under threat of criminal sanction. Throughout this period he remained active with the Rolling Stones, recording their biggest-selling studio album, Some Girls, and touring North America. Richards was tried in October 1978, pleading guilty to possession of heroin.[112][113] He was given a suspended sentence and put on probation for one year, with orders to continue treatment for heroin addiction and to perform a benefit concert on behalf of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind after a blind fan testified on his behalf.[114] Although the prosecution had filed an appeal of the sentence, Richards performed two CNIB benefit concerts at Oshawa Civic Auditorium on 22 April 1979; both shows featured the Rolling Stones and the New Barbarians.[115] In September 1979, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the original sentence.[116]

In 2016, he stated that he still occasionally drinks alcohol and consumes hashish and cannabis.[117] In 2022, he revealed that he quit smoking in 2020.[118]

Other details

Richards owns Redlands, a Sussex estate he purchased in 1966, as well as homes in Weston, Connecticut, and in the private resort island of Parrot Cay, Turks & Caicos.[119][120] His primary home is in Weston.[121][122][123] In June 2013, Richards said that he would retire with his family to Parrot Cay or Jamaica if he knew his death was coming.[124] However, in November 2016, he said, "I'd like to croak magnificently, onstage."[117] Richards is an avid reader with a strong interest in history, and owns an extensive library.[125][126] An April 2010 article revealed that Richards yearns to be a librarian.[127]

Richards is fond of shepherd's pie, a British traditional dish.[128] Stuart Cable recollected that while drummer for the Stereophonics, he was confronted by Richards because he had served himself a piece of the shepherd's pie meant for Richards.[129] The dish was also mentioned by Richards in his autobiography, advising readers to add more onions after cooking the meat filling to enhance the pie's flavour.[128]

21st century

On 27 April 2006, while in Fiji, Richards slipped off the branch of a dead tree (erroneously reported by the international press as a coconut tree)[citation needed] and suffered a head injury. He subsequently underwent cranial surgery at a New Zealand hospital.[130] The incident delayed the Rolling Stones' 2006 European tour for six weeks and forced the band to reschedule several shows. The revised tour schedule included a brief statement from Richards apologising for "falling off my perch".[131] The band made up most of the postponed dates in 2006, and toured Europe in 2007 to make up the remainder. In a video message in late 2013 as part of the On Fire tour, Richards gave his thanks to the surgeons in New Zealand who treated him, remarking, "I left half my brain there."[132]

In August 2006, Richards was granted a pardon by Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee for a 1975 reckless driving citation.[133][134]

Actor Johnny Depp has stated that his character in the movie franchise Pirates of the Caribbean is loosely based on Richards and the Warner Bros. cartoon character Pepe Le Pew,[135] with both serving as the inspiration for the manner of the character.[136][137] This combination of influences originally raised concerns with Disney corporate executives, who questioned if the character was supposed to be drunk and gay, with Michael Eisner fearing that he was "ruining the movie".[138] In the third installment of the Pirates of the Caribbean series, At World's End, Richards played Captain Edward Teague, later reprising the role in Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, the fourth film in the series (2011).[136][139]

In 2012, Richards joined the 11th annual Independent Music Awards judging panel to assist independent musicians' careers.[140]

In a 2015 interview with the New York Daily News, Richards expressed his dislike for rap and hip hop, deeming them for "tone deaf"[50] people and consisting of "a drum beat and somebody yelling over it".[141][142] In the same interview he called Metallica and Black Sabbath "great jokes" and bemoaned the lack of syncopation in most rock and roll, claiming it "sounds like a dull thud to me". He also said he stopped being a Beatles fan in 1967 when they visited the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi,[97] but this did not prevent him from playing bass in John Lennon's pickup band The Dirty Mac for a performance of the Beatles' song "Yer Blues" in the Stones' Rock and Roll Circus in December 1968.

For the weekend of 23 September 2016, Richards, together with director Julien Temple,[143] curated and hosted a three-night programme on BBC Four titled Lost Weekend.[144] Richards's choices consisted of his favourite 1960s comedy shows, cartoons and thrillers, interspersed with interviews, rare musical performances and night imagery. This 'televisual journey' was the first of its kind on British TV. Temple also directed a documentary, The Origin of the Species, about Richards's childhood in post-war England and his musical roots.

Tributes for other artists

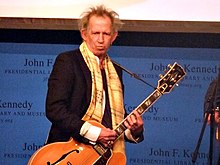

From the start of his career, Richards has made appearances to pay tribute to those artists with whom he has formed friendships and those who have inspired and encouraged him. After the earliest success of the band, who played cover songs of American blues artists, while he and Jagger were just beginning their own songwriting, the Rolling Stones visited the States to pay back, in his words, "that's where that fame bit comes in handy". Since that time, he has performed on many occasions to show appreciation toward them. Among these, he has appeared with Norah Jones in a tribute concert for Gram Parsons in 2006, playing guitar and singing a duet, "Love Hurts". On 12 March 2007 Richards attended the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremony to induct the Ronettes; he also played guitar during the ceremony's all-star jam session.[73] On 26 February 2012 Richards paid tribute to fellow musicians Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen, who were the recipients of the first annual PEN Awards for songwriting excellence at the JFK Presidential Library in Boston, Massachusetts.[145]

Richards is interviewed on screen and appears in performance footage in the 2005 documentary film Make It Funky!, which presents a history of New Orleans music and its influence on rhythm and blues, rock and roll, funk and jazz.[146] In the film, Richards said that New Orleans musicians "put the roll into rock". He also performed the Fats Domino song "I'm Ready" with the house band.[147]

In an April 2007 interview for NME magazine, music journalist Mark Beaumont asked Richards what the strangest thing he ever snorted was,[148] and quoted him as replying: "My father. I snorted my father. He was cremated and I couldn't resist grinding him up with a little bit of blow. My dad wouldn't have cared ... It went down pretty well, and I'm still alive."[149][150] In the media uproar that followed, Richards's manager said that the anecdote had been meant as a joke;[151] Beaumont told Uncut magazine that the interview had been conducted by international telephone and that he had misquoted Richards at one point (reporting that Richards had said he listens to Motörhead, when what he had said was Mozart), but that he believed the ash-snorting anecdote was true.[148][152] Musician Jay Farrar from the band Son Volt wrote a song titled 'Cocaine And Ashes', which was inspired by Richards's drug habits.[153] The incident was also referenced in the 2017 song "Mr Charisma" by The Waterboys, featuring the lyrics: "Hey Mr Charisma, what will your next trick be? Slagging Sgt Pepper, snorting your old man's bones, or falling out of a tree?"

Doris Richards, his mother, died of cancer at the age of 91 in England on 21 April 2007. An official statement released by a family representative stated that Richards kept a vigil by her bedside during her last days.[154][155]

Richards made a cameo appearance as Captain Teague, the father of Captain Jack Sparrow (played by Johnny Depp), in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End, released in May 2007,[156] and won the Best Celebrity Cameo award at the 2007 Spike Horror Awards for the role.[157] Depp has stated that he based many of Sparrow's mannerisms on Richards.[156][158][159] Richards reprised his role in Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, released in May 2011.

In March 2008, the fashion house Louis Vuitton unveiled an advertising campaign featuring a photo of Richards with his ebony Gibson ES-355, taken by photographer Annie Leibovitz. Richards donated the fee for his involvement to the Climate Project, an organisation for raising environmental awareness.[160]

On 28 October 2008, Richards appeared at the Musicians' Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Nashville, Tennessee, joining the newly inducted the Crickets on stage for performances of "Peggy Sue", "Not Fade Away", and "That'll Be the Day".[161][162]

In August 2009, Richards was ranked at No. 4 in Time magazine's list of the 10 best electric guitar players of all time.[163] In September 2009 Richards told Rolling Stone magazine that in addition to anticipating a new Rolling Stones album, he had done some recording with Jack White: "I enjoy working with Jack", he said. "We've done a couple of tracks."[164] On 17 October 2009 Richards received the Rock Immortal Award at Spike TV's Scream 2009 awards ceremony at the Greek Theatre, Los Angeles; the award was presented by Johnny Depp.[165] "I liked the living legend, that was all right", Richards said, referring to an award he received in 1989,[166] "but immortal is even better."[167]

In 2009, a book of Richards's quotations was published, titled What Would Keith Richards Do?: Daily Affirmations from a Rock 'n' Roll Survivor.[168]

In August 2007, Richards signed a publishing deal for his autobiography,[169] Life, which was released on 26 October 2010.[95]

Richards appeared in the 2011 documentary Toots and the Maytals: Reggae Got Soul, which was featured on the BBC and described as "the untold story of one of the most influential artists ever to come out of Jamaica".[170][171]

Honours

In 2010, David Fricke of Rolling Stone magazine referred to Richards as the creator of "rock's greatest single body of riffs" on guitar,[172] and the magazine ranked him fourth on its list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time.[173] Rolling Stone also lists fourteen songs he co-wrote with Jagger on its "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" list.[174]

In 2023, Tom Waits honored his friend with a poem, "Burnt Toast To Keith".[175] That same year, Richards was honoured in Dartford with a statue.[176]

Musical equipment

Guitars

Richards has a collection of approximately 3,000 guitars.[177] Even though he has used many different guitar models, Richards joked in a 1986 Guitar World interview that, no matter what model he plays, "[G]ive me five minutes and I'll make 'em all sound the same."[41] Richards has often thanked Leo Fender, and other guitar manufacturers for making the instruments, as he did during the induction ceremony of the Rolling Stones into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

| Type | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Harmony Meteor | Richards's main guitar in the early years of the Rolling Stones. It was retired in 1964 when he acquired his Les Paul Standard. | [178] |

| 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard | Richards acquired this instrument, fitted with a Bigsby tailpiece, in 1964.[179] The guitar was the first "star-owned" Les Paul in Britain and served as one of Richards's main instruments through 1966.[180] He later sold the guitar to future Rolling Stones bandmate Mick Taylor.[181] | |

| 1961 Epiphone Casino | Richards first used this instrument in May 1964, shortly before the Stones' first tour of North America. The guitar (along with the 1959 Les Paul Standard) was used frequently by Richards until 1966. | [182][183][184][185] |

| 1965 Gibson Firebird VII | During the mid-1960s Richards and Brian Jones were often seen with matching Firebird VIIs in vintage sunburst. | [186] |

| 1957 Gibson Les Paul Custom | In 1966 Richards acquired a 1957 Les Paul Custom,[187] and hand-painted it with psychedelic patterns in 1968. It served as his main stage and studio guitar from 1966 through the end of the Rolling Stones' 1971 UK tour. The guitar was probably stolen during the Nellcôte burglary in July 1971, and ended up in the hands of a collector in the mid-1990s.[citation needed] | |

| 1950s Gibson Les Paul Custom "Black Beauty" | He acquired a second late 1950s Gibson Les Paul Custom "Black Beauty" in 1969 to use in open-G tuning on the 1969 and 1970 tour.[188] | |

| Gibson ES-355s | Richards used this semi-hollow model on stage during the Rolling Stones' 1969 tour;[189] it was a favourite for both Richards and Taylor during recording sessions for Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main St.. Richards has used ES-355s on every tour since 1997. In 2006, he also unveiled a white Gibson ES-345.[190][191] | |

| Gibson Les Paul Juniors | Richards has regularly used both single-cutaway and double-cutaway Juniors since 1973. The one he is most frequently seen with is a TV-yellow double-cutaway instrument nicknamed "Dice", which he has used since 1979. On recent tours he has used this guitar for "Midnight Rambler" and "Out of Control". | [192][193] |

| 1953 Fender Telecaster | The guitar most associated with Richards, he acquired this butterscotch Telecaster in 1971. Nicknamed "Micawber", after a character in Charles Dickens' novel David Copperfield,[48] it is set up for five-string open-G tuning (-GDGBD), and has an aftermarket bridge made of brass, with individual saddles rather than the three the original bridge would have had. Richards has removed the saddle for the low string.[48] The neck pick-up has been replaced by Ted Newman Jones with a Gibson PAF humbucking pick-up, and the bridge pick-up has been replaced by a Fender lap steel pick-up (similar to a Fender Broadcaster pick-up). "Micawber" is one of Richards's main stage guitars, and is often used to play "Brown Sugar", "Before They Make Me Run", and "Honky Tonk Women".[194] | |

| 1954 Fender Telecaster | A second Telecaster, also set up by Ted Newman Jones, nicknamed both "Malcolm" and "Number 2". It is also modified for 5-string open-G tuning with the same bridge setup as Micawber and has a Gibson PAF pick-up in the neck position. It has a natural finish, and the wood grain is visible. | [194] |

| 1967 Fender Telecaster | This third Telecaster used for five-string open-G playing is a dark sunburst model, which is also fitted with a Gibson PAF pick-up. The PAF on this guitar has had its cover removed, exposing the bobbins.[194] Richards has used this guitar on stage for many songs, including "You Can't Always Get What You Want" and "Tumbling Dice".[195] | |

| 1958 Fender Stratocaster | Fellow Rolling Stones guitarist Ronnie Wood gave Richards his 1958 Mary Kaye Signature Stratocaster after the band's 1982 tour. The guitar is finished in see-through blond and fitted with gold hardware.[194] Richards has used this guitar onstage for "You Don't Have to Mean It" and "Miss You".[citation needed] | |

| 1975 Fender Telecaster Custom | Richards first used this guitar on the Rolling Stones' 1975 Tour of the Americas, and it was his main stage and recording guitar until 1986. It was later adapted for five-string open-G tuning, and reappeared on stage in 2005. | [196] |

| Ampeg Dan Armstrong plexiglas guitar | This Dan Armstrong guitar was given to Richards during rehearsals for the 1969 tour[197] and became one of his main stage and studio guitars until it was stolen during the Nellcôte burglary in July 1971. For the 1972 tour, he purchased two new Dan Armstrong guitars, which he only used during the first couple of shows. Fitted with a custom-made "sustained treble" humbucker pick-up, he used the guitar mainly in standard tuning. It can be heard on "Carol", "Sympathy for the Devil", and "Midnight Rambler" on Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out. On the 1970 tour Richards added a second Dan Armstrong guitar fitted with a "rock treble" pick-up.[citation needed] | |

| Gibson Hummingbird | Played since the late 1960s. | [198] |

| Zemaitis Five-String | Custom-made in 1974 by British luthier Tony Zemaitis, the guitar nicknamed both "Macabre" and "the Pirate Zemaitis" was decorated with skulls, a pistol, and a dagger. Richards used it as his main open-G guitar from 1975 to 1978, when it was destroyed in a fire at his rented Los Angeles home. Richards used a Japanese-made replica on the 2005–2006 tour. | [199] |

| Newman-Jones custom guitars | Texas luthier Ted Newman-Jones made several custom five-string instruments that Richards used on the 1973 tours of Australasia and Europe. Richards used another Newman-Jones custom model on the 1979 New Barbarians tour. | [200] |

Amplifiers

Richards's amplifier preferences have changed repeatedly. However, he is a long-time proponent of using low-powered amps in the studio. He achieves clarity plus distortion by using two amps: a larger one (such as a Fender Twin) which runs clean, along with a Fender Champ, which is overdriven.[201] To record "Crosseyed Heart", Richards used a stock tweed Fender Champ with 8" speaker coupled with a modified Fender Harvard.[202]

Some of his notable amplifiers are:

- Mesa/Boogie Mark 1 A804 – Used between 1977 and 1993, this 100-watt 1x12" combo is finished in hardwood with a wicker grille. It can be heard on the Rolling Stones albums Love You Live, Some Girls, Emotional Rescue, and Tattoo You, as well as on Richards's two solo albums, Talk is Cheap and Main Offender. This amplifier was handcrafted by Randall Smith and delivered to Richards in March 1977.[203]

- Fender Twin – Since the 1990s, Richards has tended to use a variety of Fender "tweed" Twins on stage. Containing a pair of 12" speakers, the Fender Twin was, by 1958, an 80-watt all-tube guitar amplifier. Richards has utilised a pair of Fender Twins "to achieve his signature clean/dirty rhythm and lead sound."[204]

- Fender Dual Showman – First acquired in 1964. Richards made frequent use of his blackface Dual Showman amp through mid-1966. Used to record The Rolling Stones, Now!, Out of Our Heads, December's Children, and Aftermath before switching over to various prototype amplifiers from Vox in 1967 and the fairly new Hiwatt in 1968.[205]

- Ampeg SVT – With 350 watts, the Ampeg SVT amp's midrange control, midrange shift switch, input pads, treble control with bright switch shaped the guitar sound of 1970s live Stones. Used live by the Stones for guitar, bass, and organ (Leslie) from 1969 to 1978. For a brief period in 1972 and 1973, Ampeg V4 and VT40 amps shared duties in the studio with Fender Twin and Deluxe Reverb amps.[205]

Effects

In 1965, Richards used a Gibson Maestro fuzzbox to achieve the distinctive tone of his riff on "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction";[206] the success of the resulting single boosted the sales of the device to the extent that all available stock had sold out by the end of 1965.[207] In the 1970s and early 1980s Richards frequently used guitar effects such as a wah-wah pedal, a phaser, and a Leslie speaker,[208] but he has mainly relied on combining "the right amp with the right guitar" to achieve the sound he wants.[209]

Discography

- Talk Is Cheap (1988)

- Main Offender (1992)

- Crosseyed Heart (2015)

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Man on Horseback | Soldier | |

| 2002 | The Simpsons | Himself | "How I Spent My Strummer Vacation" (voice) |

| 2007 | Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End | Captain Teague | Awarded Scream Award for Best Cameo |

| 2007 | Keith Richards: Under Review | Keith Richard/Richards | |

| 2011 | Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides | Nominated—People's Choice Award for Favorite Ensemble Movie Cast Nominated—Scream Award for Best Cameo | |

| 2011 | Toots and the Maytals: Reggae Got Soul | Himself | Documentary[170] |

| 2012 | Rolling Stones: One More Shot | Himself | TV movie |

| 2015 | Keith Richards: Under the Influence | Himself | TV movie |

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ In the early years of the band's career, the name "Keith" was widely pronounced and written in the press and on Stones' album covers, as "Keef", a case of th-fronting that would eventually fade. See McNair (2005), di Perna (2012). In mid-1963, as part of his effort to rework the Rolling Stones' image, Andrew Loog Oldham advised that Richards drop the s from his name, making it Keith Richard.[1][2] The change was not official and was assumed only as a stage name.[3] In 1978, Richards switched back to using his legal name in all public and private contexts.[4]

References

Citations

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Salewicz 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Bockris 2003, pp. 44, 223.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 223.

- ^ "The 250 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". Rolling Stone. 13 October 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ Richards & Fox 2010, p. 21.

- ^ a b Bockris 2003, p. 17-18.

- ^ Binns, Daniel (24 July 2012). "HISTORY: Keith Richards's Walthamstow roots". This Is Local London. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Rowland, Paul (30 October 2006). "Exhibition of Welsh pirate portrait based on Rolling Stone". Western Mail. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Richards & Fox 2010, p. 500.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 29–30.

- ^ Desert Island Discs, BBC Radio 4, 25 October 2015

- ^ a b Noisey Staff (23 October 2015). "Here's the Story of the First Time Keith Richards Played the Guitar". Noisey. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 33.

- ^ St. Michael 1994, p. 75.

- ^ Richards & Fox 2010, p. 72.

- ^ Stevens, Jenny (16 December 2013). "Spot where The Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger and Keith Richards met to be marked with plaque". NME. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 20, 22.

- ^ Keith Richards – My life as a Rolling Stone – 2022

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Wells, Dennis (6 July 1995). "Dartford and Swanley Informer". Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bockris 2003, p. 27-28.

- ^ "Plaque to mark Jagger-Richards meet". BBC News. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Empire, Kitty (26 May 2018). "Rolling Stones review – satisfaction guaranteed from rock's old stagers". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Rej 2006, p. 263.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 34-35.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 38.

- ^ "Keith Richards – The Origin Of The Species – Media Centre". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "I'm looking at this guy and I..., I know you, what you've got under your arm is worth robbing" "Keith Richards – The Origin of the Species (Julien Temple) – BBC Two". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Fricke, David (3 December 2010). "Keith Richards". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "When Mick met Keith". BBC News. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ It's Only Rock 'n' Roll, The Ultimate Guide to the Rolling Stones, James Karnbach and Carol Bernson, Facts on File Inc., New York, NY., 1997

- ^ Ian Stewart Interview by Lisa Robinson, Creem Magazine, June 1976

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (18 April 2009). "So, what did you learn at school today: do art colleges still produce inventive pop stars". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 327-328.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Davis 2001, p. 58; Salewicz 2001, p. 58; Egan 2006, p. 23; Jucha 2019, p. 14

- ^ Day, Elizabeth (13 November 2011). "The Rolling Stones: that 50-year itch". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Santoro, Gene (1986). "The Mojo Man Rocks Out". Guitar World, March 1986, reprinted (2006) in Guitar Legends: The Rolling Stones.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 56.

- ^ "Keith on keeping on – interview with Keith Richards". Chrisspedding.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Sabella Recording Studios: Keith Richards Interview". Sabellastudios.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Jagger et al. 2003, p. 39, 180.

- ^ Guitar World, October 2002. Interview: "Heart Of Stone"

- ^ a b c Hunter 2012, p. 141.

- ^ a b Obrecht, Jas (1992). "Keith Richards Comes Clean on Distortion and the Meaning of Music". Guitar Player. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ a b Kinos-Goodin, Jesse (17 September 2015). "Keith Richards explains the 5-string guitar: '5 strings, 3 notes, 2 hands and 1 asshole'". CBC Music. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ di Perna, Alan (6 January 2012). "Keith Richards Looks Back on 40 Rocking Years with the Rolling Stones". guitarworld. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Myers, Marc (11 December 2013). "Keith Richards: 'I Had a Sound in My Head That Was Bugging Me'". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 14 May 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Booth 1994, p. 173-174.

- ^ Dolan, Jon; Doyle, Patrick; Grow, Kory; Hermes, Will; Sheffield, Rob (10 September 2015). "Keith Richards' 20 Greatest Songs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Appleford 2000, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Jagger et al. 2003, p. 290.

- ^ Paulson, Dave (10 October 2021). "The Rolling Stones spend the night with Nashville in explosive stadium concert". The Tennessean. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ The Rolling Stones (2006). Shine a Light (DVD released 2008). Universal.

- ^ Oldham 2000, p. 249-251.

- ^ Elliott 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Elliott 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Booth 1994, p. 51.

- ^ a b c McPherson, Ian. "Jagger/Richards: Songwriters". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ "Mick Jagger & Keith Richards". ABKCO Music & Records, Inc. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Savage, Mark (19 November 2020). "Keith Richards: 'I'll celebrate the Stones' 60th anniversary in a wheelchair'". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ "Inductees: Keith Richards". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 27 March 2003. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 224.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 130.

- ^ Paytress 2009, p. 316.

- ^ Loewenstein 2014, p. 138.

- ^ Leggett, Steve "Wingless Angels Biography", AllMusic, Macrovision Corporation. Retrieved 29 November 2009

- ^ Christgau 1988, pp. 60–66.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zentgraf, Nico. "The Complete Works of the Rolling Stones 1962–2008". Archived from the original on 19 March 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ^ "Official Keith Richards website". Keithrichards.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ The Rolling Stones, the Dirty Mac (1968). Rock and Roll Circus (DVD released 2004). ABKCO Films.

- ^ Berry, Chuck; Richards, Keith (1986). Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll (DVD released 2006). Universal City Studios Inc.

- ^ "47th Annual GRAMMY Awards". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. 28 November 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Four Flicks – Disc 4 (Arena Show) – in the extras section for Start Me Up

- ^ Saperstein, Pat (14 June 2017). "Anita Pallenberg, Actress and Longtime Girlfriend of Keith Richards, Dies at 73". Variety. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 343.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 392.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 242–246.

- ^ Richards & Fox 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Bockris, Victor (1993). Keith Richards: The Biography. Poseidon Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780671875909.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (25 October 2015). "I owe it all to my mum's impeccable taste in music says rocker Keith Richards". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (14 June 2017). "Rob Sheffield: Why Anita Pallenberg Was Queen of the Underground". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Keith Richards writing children's book with daughter". The Independent. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Five grandchildren". KeithRichards.com Official Website. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Richards, Theodora (11 September 2024). "Oscar and I's son Augustus LeBeau Richards Burnett came jnto the wild world on May21st". Instagram.

- ^ Richards, Alexandra (27 May 2021). "Our little bundle of love, Arlowe Mae Naudé blessed us with her presence May 19th". Instagram.

- ^ "Jagger describes love/hate relationship with Richards". IOL. 8 October 2005. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Entertainment | Stones row over Jagger knighthood". BBC News. 4 December 2003. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (12 October 1988). "The Pop Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ "Johnny Depp, Keith Richards to Begin Fourth 'Pirates' – Mick Jagger rumored for fourth 'Pirates'". My Fox Houston. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (19 October 2010). "Keith Richards on Brian Jones, Mick Jagger and the New Memoir, 'Life'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Bloxham, Andy (15 October 2010). "Keith Richards: 'Mick Jagger has been unbearable since 1980s'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b Farber, Jim (3 September 2016). "Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards calls Metallica and Black Sabbath 'great jokes,' says rap is for 'tone-deaf people' in free-wheeling interview". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 213-214.

- ^ Deevoy, Adrian (August 1994). "Ladies and Gentlemen, the Interesting Old Farts". Q. EMAP Metro. p. 91.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 133–135, 215–216, 280–283.

- ^ a b Flippo 1985, p. 177-178.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 243-245.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 276.

- ^ "Mick goes to jail". musicpilgrimages.com. 11 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Keith goes to jail". musicpilgrimages.com. 14 October 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 277.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 286.

- ^ Booth 2000, p. 278–279.

- ^ Flippo 1985, p. 67–68.

- ^ Bockris 2003, p. 261–263.

- ^ Flippo 1985, p. 134.

- ^ Wyman 2002, p. 453.

- ^ Flippo 1985, p. 134–136.

- ^ Flippo 1985, p. 178.

- ^ O'Neill Jr, Lou (29 May 1979). "Back Pages: Will Canada Get Its Pound of Flesh from Keith Richards?". Circus.

- ^ Greenspan 1990. p. 518.

- ^ a b "The Rolling Stones' New Blues: Inside Their Roots Revival, Bright Future". Rolling Stone. 3 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ DeSantis, Rachel (15 March 2022). "Keith Richards Reveals He Quit Smoking, Now Has 'More Stamina': 'Just Put the Hammer on It'". People. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Malle, Chloe (18 July 2012). "Anything Goes: Keith Richards and Patti Hansen". Vogue. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013.

- ^ Mueller, Andrew (April 2008). "Mick's a Maniac: Interview with Keith Richards". Uncut. p. 38.

- ^ McNair, James (20 August 2005). "Keith Richards: Being, Keef". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ David, Mark (18 March 2016). "Keith Richards Gets No Satisfaction From New York City Penthouse". Variety. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Renzoni 2017, p. 123.

- ^ "Keith Richards plans to retire in the Caribbean". Toronto Sun. 17 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- ^ Braun, Liz (8 March 2008). "Richards Turns a New Page". Edmonton Sun. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Ellis, Seebohm & Sykes 1995, pp. 209–212.

- ^ Harlow, John (4 April 2010). "It's only books 'n' shelves but I like it". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ a b "8 pop stars and their strange food obsessions",BBC Music,12/1/2017

- ^ Lyons, Beverley (6 April 2009). "New book from former Stereophonics lifts lid on his pie-eyed tour with Rolling Stones". Daily Record. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Kiwi Doctor Rolls with the Stones". Sunday Star Times. 10 February 2008. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ "Keith Richards Is Given the All Clear to Get Back to Work As Stones Announce New Itinerary for European Shows". RollingStones.com. 2 June 2006. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ "Keith Richards' message to NZ". The New Zealand Herald. 5 December 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- ^ "Huckabee prepares pardon papers for rocker Keith Richards". Arkansas News Bureau. 20 July 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- ^ "Not My Job: Mike Huckabee (Wait Wait...Don't Tell Me!)". NPR. 8 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2 July 2009.

- ^ Zoromski, Michelle (11 July 2003). "A Conversation with Johnny Depp". IGN. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Johnny Depp 'sponged' from Keith Richards for 'Pirates Of The Caribbean'". NME. 13 May 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Keith Richards and Johnny Depp: Blood Brothers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (30 November 2010). "Disney bosses thought Jack Sparrow drunk or gay, says Johnny Depp". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Paul McCartney Reveals 'Pirates of the Caribbean' Character". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "11th Annual IMA Judges". Independentmusicawards.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Mokoena, Tshepo (4 September 2015). "Keith Richards: 'Rap showed there are tone-deaf people out there'". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (3 September 2015). "Keith Richards: Rap Is for 'Tone-Deaf People'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "BBC Four – Keith Richards' Lost Weekend, Praise and Damnation". BBC. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Daly, Rhian (23 September 2016). "Keith Richards' Lost Weekend Playlist". NME. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Shanahan, Mark; Goldstein, Beth (26 February 2012). "Leonard Cohen and Chuck Berry celebrated at the JFK Library". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ "IAJE What's Going On". Jazz Education Journal. 37 (5). Manhattan, Kansas: International Association of Jazz Educators: 87. April 2005. ISSN 1540-2886. ProQuest 1370090.

- ^ Make It Funky! (DVD). Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2005. ISBN 9781404991583. OCLC 61207781. 11952.

- ^ a b "Snortergate: The True Story (Interview with Mark Beaumont)". Uncut. September 2007. p. 55.

- ^ "Exclusive: Keith Richards: 'I Snorted My Dad's Ashes'". NME. UK. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Keith Richards: Read the Interview the World Is Talking About". NME. UK. 4 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Did Keith Richards Really Snort His Dad's Ashes? No – It Was A Joke!". MTV. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008.

- ^ Doyle, Tom (September 2007). "Keith Richards: The Mojo Interview". Mojo. EMAP Performance Ltd. p. 60.

- ^ "Son Volt's Jay Farrar Inspired by Keith Richards' Drug Habits 'Spinner 2009". Spinner. 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Keith Richards' mother dies". ABC News. 24 April 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ "Keith Richards' Mum Dies". MTV Music Television. 24 April 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ a b Wild, Davido (31 May 2007). "Johnny Depp & Keith Richards: Pirates of the Caribbean's Blood Brothers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ^ "Keith Wins Spike Award". RollingStones.com. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ Mundinteractivos (31 October 2006). "El retrato de Keith Richards que inspiró a Johnny Depp, expuesto en una galería de Londres". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016.

- ^ "Pirate Keith Richards – Paul Karslake FRSA". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Keith Richards the New Face of Louis Vuitton". The Sydney Morning Herald. 5 March 2008. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ "Keith Richards, Percy Sledge, others honour new Musician Hall of Fame inductees". The Tennessean. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Hall of Fame Honour for Booker T". BBC News. 29 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Dave on 2 (24 August 2009). "Fretbase, Time Magazine Picks the 10 Best Electric Guitar Players". Fretbase.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Greene, Andy (2 September 2009). "Keith Richards on Recording With Jack White, New Stones LP". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 5 September 2009. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ "Spike TV press release". Spike.com. 15 October 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "The 1st International Rock Awards 1989". waddywachtelinfo.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ^ Cohen, Sandy (18 October 2009). "Depp, Richards Light Up Spike TV's 'Scream 2009". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- ^ Hernandez, Raoul (17 July 2009). "What Would Keith Richards Do?". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (1 August 2007). "A Rolling Stone Prepares to Gather His Memories". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Toots and the Maytals: Reggae Got Soul". BBC Four (documentary). Directed by George Scott. 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2016. "Toots and the Maytals: Reggae Got Soul". Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Tootsandthemaytals. "Toots & The Maytals – Reggae Got Soul – Documentary Trailer." YouTube. 15 August 2013. 15 December 2016. "Toots and the Maytals: Reggae Got Soul". YouTube. 15 August 2013. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Fricke, David (3 December 2010). "100 Greatest Guitarists: David Fricke's Picks". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "Rolling Stone: 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time". 22 November 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 9 December 2004. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Bonner, Michael (18 December 2023). "Read Tom Waits' new poem to Keith Richards". Uncut.

- ^ Sherwood, Harriet (9 August 2023). "Statues of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards unveiled in home town of Dartford". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ Miller 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Bacon 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Burrluck, Dave (September 2007). "The Keithburst Les Paul". Guitarist Magazine: 55–58.

- ^ Bacon 2002, pp. 38, 50, 123.

- ^ "Keith Richards 1959 Les Paul Standard". Richard Henry Guitars. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Epiphone Casino Electric Guitar". Vintageguitars.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Epiphone News: Rolling Stones at 50". Epiphone.com. 3 February 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Epiphone: 1961 50th Anniversary Casino". Epiphone.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Epiphone Casino". Epiphone.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012.

- ^ "9 Guitars Keith Richards Played That Definitely WEREN'T Telecasters". Sonicstate.com.

- ^ "The Ed Sullivan Show". 20. Episode 884. 11 September 1966.

- ^ "9 Guitars Keith Richards Played That Definitely WEREN'T Telecasters". Sonicstate.com.

- ^ The Rolling Stones (1969). Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out (re-release) (DVD released 2009). ABKCO.

- ^ The Rolling Stones (1997). Bridges to Babylon (DVD released 1999). Warner Home Video.

- ^ The Rolling Stones (June 2005). The Biggest Bang (DVD released 2007). Universal Music Operations.

- ^ Leonard, Michael (12 July 2012). "Satisfaction Guaranteed: Keith Richards' Favorite Gibsons". Gibson.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Drozdowski, Ted (18 May 2010). "Exile Week: Exile on Main Street and the Gibson Les Paul Standard Dynasty of Keith Richards and Mick Taylor". Gibson.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Rolling Stones – Keith Richards Guitar Gear Rig and Equipment". Archived from the original on 8 December 2009.

- ^ "Keith Richards's Gear List: Fender Telecaster (Duplicate)". Equipboard.com.

- ^ "Keith Richards's Gear List: Fender Telecaster Custom". Equipboard.com.

- ^ "Through The Years, Clearly: Dan Armstrong Series". Ampeg. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Keith Richards' Guitars and Gear". GroundGuitar. 20 June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ "Precious metal: the history of Zemaitis guitars". MusicRadar. 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Untitled". Billboard. 28 December 1989.

- ^ Egan 2013, p. 232.

- ^ di Perna, Alan (29 October 2015). "Keith Richards' Guitar Tech Reveals Keef's Studio Rig". Guitar World. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Keef's '77 Mar k 1 El Mocambo Boogie". Archived from the original on 30 December 2008.

- ^ "1958 Fender Strat & 1959 Fender Twin". Premierguitar.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Keith Richards's Guitars and Amps". Equipboard.com.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (2006). "No Stone Unturned". Guitar Legends: The Rolling Stones. p. 12.

- ^ "Sold on Song: (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Dalton 1981, p. 163.

- ^ Wheeler, Tom (December 1989). "Keith Richards: Not Fade Away". Guitar Player. New Bay Media LLC.

Works cited

- Appleford, Steve (2000). The Rolling Stones: Rip This Joint: The Story Behind Every Song. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-281-2.

- Bacon, Tony (2000). Fuzz & Feedback: Classic Guitar Music of the '60s. Miller Freeman Books. p. 13. ISBN 0-87930-612-2.

- Bacon, Tony (2002). 50 Years of the Gibson Les Paul. Backbeat. ISBN 0-87930-711-0. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- Bockris, Victor (2003). Keith Richards: The Biography (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81278-9. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017.

- Booth, Stanley (1994). Keith: Till I Roll Over Dead. Headline Book Publishing. ISBN 0-7472-0770-4.

- Booth, Stanley (2000). The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (second ed.). A Capella Books. ISBN 1-55652-400-5.

- Christgau, Robert (1988). "Chuck Berry". In Decurtis, Anthony; Henke, James (eds.). The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll: The Definitive History of the Most Important Artists and Their Music. New York: Random House. pp. 60–66. ISBN 0-679-73728-6.

- Dalton, David (1981). The Rolling Stones: The First Twenty Years. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 163. ISBN 0-394-52427-6.

- Davis, Stephen (2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. New York City: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0312-9.

- Egan, Sean (2006). The Rough Guide to the Rolling Stones. New York City: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-719-9.

- Egan, Sean (1 September 2013). Keith Richards on Keith Richards: Interviews and Encounters. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613747919. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016 – via Google Books.

- Elliott, Martin (2002). The Rolling Stones: Complete Recording Sessions 1962–2002. Cherry Red Books. ISBN 1-901447-04-9.

- Ellis, Estelle; Seebohm, Carol; Sykes, Christopher Simon (1995). At Home with Books: How Booklovers Live with and Care for Their Libraries. Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59500-1.

- Flippo, Chet (1985). On the Road with the Rolling Stones. Doubleday/Dolphin. ISBN 0-385-19374-2.

- Hunter, Dave (15 October 2012). The Fender Telecaster: The Life and Times of the Electric Guitar That Changed the World. Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760341384. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016 – via Google Books.

- Jagger, Mick; Richards, Keith; Watts, Charlie; Wood, Ronnie (2003). According to the Rolling Stones. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-4060-3.

- Jucha, Gary J. (2019). Rolling Stones FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Bad Boys of Rock. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-5074-1.

- Loewenstein, Prince Rupert (2014). A Prince Among Stones: That Business with the Rolling Stones and Other Adventures. A & C Black. ISBN 9781408831342.

- Miller, Heather (1 September 2010). The Rolling Stones: The Greatest Rock Band. Enslow Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9780766032316.

- Oldham, Andrew Loog (2000). Stoned. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-27094-1.

- Paytress, Mark (15 December 2009). Rolling Stones: Off The Record: Off the Record. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857121134.

- St. Michael, Mick (1994). In His Own Words: Keith Richards. Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-3634-X.

- Rej, Bent (2006). The Rolling Stones: in the beginning. Great Britain: Firefly Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55407-230-9.

- Renzoni, Tony (2017). Connecticut Rock 'n' Roll: A History. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781625858801.

- Richards, Keith; Fox, James (26 October 2010). Life. Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0316034418.

- Salewicz, Chris (2001). Mick & Keith. London: Orion. ISBN 978-0-7528-1858-0.

- Thompson, Dave (2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. ECW Press. ISBN 9781550226188.

- Wyman, Bill (2002). Rolling With the Stones. DK Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-9998-3.

External links

- Official website

- Keith Richards at AllMusic

- Keith Richards at IMDb

- Keith Richards on National Public Radio in 2010

- Keith Richards at the Songwriters Hall of Fame

- CBC Archives Richards's trial and sentencing in 24 October 1978 and 16 April 1979

- Keith Richards

- 1943 births

- 20th-century English male singers

- 20th-century English singers

- 21st-century English male singers

- 21st-century English singers

- British rhythm and blues boom musicians

- English autobiographers

- English blues guitarists

- English male guitarists

- English people of Welsh descent

- English rock guitarists

- English rock singers

- English male singer-songwriters

- English singer-songwriters

- English people convicted of drug offences

- English record producers

- Ivor Novello Award winners

- British rhythm guitarists

- British lead guitarists

- Living people

- Musicians from Kent

- People from Dartford

- Recipients of American gubernatorial pardons

- The Dirty Mac members

- The Rolling Stones members

- Virgin Records artists

- English expatriate musicians in the United States

- English male film actors

- People from Weston, Connecticut