Lobbying

Lobbying is a form of advocacy, which lawfully attempts to directly influence legislators or government officials, such as regulatory agencies or judiciary.[1] Lobbying involves direct, face-to-face contact and is carried out by various entities, including individuals acting as voters, constituents, or private citizens; corporations pursuing their business interests; nonprofits and NGOs through advocacy groups to achieve their missions; and legislators or government officials influencing each other in legislative affairs.

Lobbying or certain practices that share commonalities with lobbying are sometimes referred to as government relations, or government affairs and sometimes legislative relations, or legislative affairs. It is also an industry known by many of the aforementioned names, and has a near complete overlap with the public affairs industry. Lobbyists may fall into different categories: amateur lobbyists, such as individual voters or voter blocs within an electoral district; professional lobbyists who engage in lobbying as a business or profession; and government relations support staff who work on behalf of professional lobbyists but may not actively engage in direct influencing or face-to-face meetings with targeted individuals to the extent required for registration as lobbyists, operating within the same professional circles as registered lobbyists.

Professional lobbyists are people whose business is trying to influence legislation, regulation, or other government decisions, actions, or policies on behalf of a group or individual who hires them. Nonprofit organizations whether as professional or amateur lobbyists can also lobby as an act of volunteering or as a small part of their normal job. Governments often define "lobbying" for legal purposes, and regulate organized group lobbying that has become influential.

Criticism

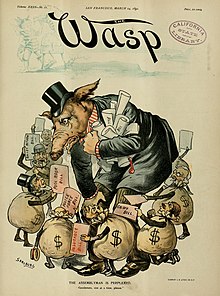

[edit]The ethics and morals involved with legally lobbying or influence peddling are controversial. Lobbying can, at times, be spoken of with contempt, when the implication is that people with inordinate socioeconomic power are corrupting the law in order to serve their own interests. When people who have a duty to act on behalf of others, such as elected officials with a duty to serve their constituents' interests or more broadly the public good, can benefit by shaping the law to serve the interests of some private parties, a conflict of interest exists. Many critiques of lobbying point to the potential for conflicts of interest to lead to agent misdirection or the intentional failure of an agent with a duty to serve an employer, client, or constituent to perform those duties. The failure of government officials to serve the public interest as a consequence of lobbying by special interests who provide benefits to the official is an example of agent misdirection.[2] That is why lobbying is seen as one of the causes of a democratic deficit.[3] Politicians tend to vote against the preferred position of their constituency when there is more special interest money and less attention to politics.[4]

Etymology

[edit]That architectural sense of lobby is believed to originate from the medieval Latin lobia or lobium, which refers to a gallery, hall, or portico. This architectural sense was later adopted to describe the practice of advocating or debating in such spaces.[5]

In a report carried by the BBC, an OED lexicographer has shown that "lobbying" finds its roots in the gathering of Members of Parliament and peers in the hallways ("lobbies") of the United Kingdom Houses of Parliament before and after parliamentary debates where members of the public can meet their representatives.[6]

One story held that the term originated at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., where it was supposedly used by President Ulysses S. Grant to describe the political advocates who frequented the hotel's lobby to access Grant—who was often there in the evenings to enjoy a cigar and brandy—and then tried to buy the president drinks in an attempt to influence his political decisions.[7] Although the term may have gained more widespread currency in Washington, D.C., by virtue of this practice during the Grant Administration, the OED cites numerous documented uses of the word well before Grant's presidency, including use in Pennsylvania as early as 1808.[7]

The term "lobbying" also appeared in print as early as 1820:[8]

Other letters from Washington affirm, that members of the Senate, when the compromise question was to be taken in the House, were not only "lobbying about the Representatives' Chamber" but also active in endeavoring to intimidate certain weak representatives by insulting threats to dissolve the Union.

— April 1, 1820

Overview

[edit]

Governments often[quantify] define and regulate organized group lobbying[9][10][11][12] as part of laws to prevent political corruption and by establishing transparency about possible influences by public lobby registers.

Lobby groups may concentrate their efforts on the legislatures, where laws are created, but may also use the judicial branch to advance their causes. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, for example, filed suits in state and federal courts in the 1950s to challenge segregation laws. Their efforts resulted in the Supreme Court declaring such laws unconstitutional.[13]

Lobbyists may use a legal device known as amicus curiae (lit. 'friend of the court') briefs to try to influence court cases. Briefs are written documents filed with a court, typically by parties to a lawsuit. Amici curiae briefs are briefs filed by people or groups who are not parties to a suit. These briefs are entered into the court records and give additional background on the matter being decided upon. Advocacy groups use these briefs both to share their expertise and to promote their positions.[14]

The lobbying industry is affected by the revolving door concept, a movement of personnel between roles as legislators and regulators and roles in the industries affected by legislation and regulation, as the main asset for a lobbyist is contacts with and influence on government officials.[15][16] This climate is attractive for ex-government officials.[17] It can also mean substantial monetary rewards for lobbying firms, and government projects and contracts worth in the hundreds of millions for those they represent.[18][19]

The international standards for the regulation of lobbying were introduced at four international organizations and supranational associations: 1) the European Union; 2) the Council of Europe; 3) the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; 4) the Commonwealth of Independent States.[20]

Methods

[edit]In 2013, the director general of the World Health Organization, Margaret Chan, illustrated the methods used in lobbying against public health:[21]

Efforts to prevent noncommunicable diseases go against the business interests of powerful economic operators. In my view, this is one of the biggest challenges facing health promotion. [...] it is not just Big Tobacco anymore. Public health must also contend with Big Food, Big Soda, and Big Alcohol. All of these industries fear regulation, and protect themselves by using the same tactics. Research has documented these tactics well. They include front groups, lobbies, promises of self-regulation, lawsuits, and industry-funded research that confuses the evidence and keeps the public in doubt. Tactics also include gifts, grants, and contributions to worthy causes that cast these industries as respectable corporate citizens in the eyes of politicians and the public. They include arguments that place the responsibility for harm to health on individuals, and portray government actions as interference in personal liberties and free choice. This is formidable opposition. [...] When industry is involved in policy-making, rest assured that the most effective control measures will be downplayed or left out entirely. This, too, is well documented, and dangerous. In the view of WHO, the formulation of health policies must be protected from distortion by commercial or vested interests.

Lobbying can be categorized as inside lobbying, which directly interacts with decision-makers, or outside lobbying, which pressures decision-makers through mobilization of public opinion.[22]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

In pre-modern political systems, royal courts provided incidental opportunities for gaining the ear of monarchs and their councilors.[23]

Lobbying by country

[edit]Australia

[edit]Since the 1980s, lobbying in Australia has grown from a small industry of a few hundred employees to a multi-billion dollar per year industry. What was once the preserve of big multinational companies and at a more local level (property developers, for example Urban Taskforce Australia) has morphed into an industry that employs more than 10,000 people and represents every facet of human endeavour.[24]

Academic John Warhurst from the Australian National University noted that over this time, retired politicians have increasingly turned political lobbyists to leverage their networks and experience for private gain. In 2018 he noted that two of the top three Howard government ministers had become lobbyists: Alexander Downer and Peter Costello, and that the trend could be traced back to the Hawke Government of 1983. Mick Young stated that by 1983 the lobbying profession was an established part of the democratic political process in Canberra. Warhurst attests that by 2018, "political leader-lobbyists" were an established part of the same process. During the 1980s, political leaders traded on their own names, like Bob Hawke, or joined the "respectable" end of the lobbying spectrum, working for law firms or banks, like former New South Wales premiers Nick Greiner and Bob Carr. In 2008, Alexander Downer formed the lobbying firm Bespoke Approach, along with former Labor minister Nick Bolkus and Ian Smith, who is married to former Australian Democrats leader, Natasha Stott-Despoja. Peter Costello carried two former staffers to work with him in his lobbying firm, ECG Consulting: Jonathan Epstein and David Gazard. Politicians can become exposed to allegations of conflicts of interest when they both lobby and advise governments. Examples include Peter Costello.[25]

Political party staff often form lobbying firms or dominate their ranks. Former Howard chief-of-staff Grahame Morris is director of Barton Deakin Government Relations. His colleagues there include David Alexander (former Costello staffer), Sallyanne Atkinson (former Lord Mayor of Brisbane and former federal Liberal Party candidate), Howard staffer John Griffin and former New South Wales Liberal Party leader, Peter Collins. The Labor "sister" company is Hawker Britton, so named as both firms are owned by STW Group. In 2013, Hawker Britton had 113 client companies on its books.[26]

In 2013, there were just under 280 firms on the Federal Australian Register of Lobbyists. Steve Carney of Carney Associated says that lobbyists "try to leave no thumbprints on the glass, no footprints in the sand. The best lobbying is when nobody knows you were there."[26] Mark Textor of campaign advisory group Crosby Textor describes political lobbying as a "pathetic miserable industry".[26]

Supermarket sector lobbying

[edit]Supermarket chains in Australia engage lobbying firms with political weight in their ranks. Australian Supermarket giant Coles is represented by both ECG Consulting and Bespoke Approach, while its own parent company, Wesfarmers, has former West Australian premier Alan Carpenter in charge of corporate affairs. Competitor Woolworths has a government relations team composed of former Labor and Liberal advisers, under the direction of a former leader of the National Party, Andrew Hall. Aldi engages GRA (Government Relations Australia), one of Australia's largest lobbying firms, whose staff includes former Federal Labor treasurer, John Dawkins.[25]

Public lobbyist registers

[edit]A register of federal lobbyists is kept by the Australian Government and is accessible to the public via its website.[27] Similar registers for State government lobbyists were introduced between 2007 and 2009 around Australia. Since April 2007 in Western Australia, only lobbyists listed on the state's register are allowed to contact a government representative for the purpose of lobbying.[28] Similar rules have applied in Tasmania since 1 September 2009[29] and in South Australia and Victoria since 1 December 2009.[30][31] A criticism of the lobbyist register is that it only captures professional third-party lobbyists, not employees of companies which directly lobby government. An example of this is BHP, which employs Geoff Walsh, a key advisor to Bob Hawke as an in-house lobbyist.[26]

In 2022, The Mercury published a complete list of lobbyists registered at the Tasmanian Parliament. The field was dominated by former politicians, advisers and journalists in 2016.[32]

Azerbaijan

[edit]

Bahrain

[edit]In December 2022, Bahrain's lobbying efforts reflected in a report by The Guardian, which involved the name of a senior Czech MEP Tomáš Zdechovský. The controversy concerned the European Parliament's "friendship groups", the unofficial bodies operating with no formal regulations and sometimes under sponsored lobbyists and foreign governments. The European Parliament was preparing to vote on a resolution to call for a release of a Bahraini political prisoner Abdulhadi al-Khawaja. However, chair of European Parliament's Bahrain friendship group, Zdechovský came under questions for visiting Bahrain in April 2022, without declaring. In a separate resolution, Zdechovský's EPP failed to call for Khawaja's release and instead called him a "political opponent". Director of BIRD, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei accused the Czech MEP of acting as a mouthpiece for Bahrain.[38]

Canada

[edit]Canada maintains a Registry of Lobbyists.[39] Over 5,000 people now working as registered lobbyists at Canada's federal level. Lobbying began as an unregulated profession, but since the late 20th century has been regulated by the government to increase transparency and establish a set of ethics for both lobbyists, and those who will be lobbied. Canada does not require disclosure of lobbyist spending on lobbying activities.[40]

European Union

[edit]

The first step towards specialized regulation of lobbying in the European Union was a Written Question tabled by Alman Metten, in 1989. In 1991, Marc Galle, Chairman of the Committee on the Rules of Procedure, the Verification of Credentials and Immunities, was appointed to submit proposals for a Code of conduct and a register of lobbyists. Today lobbying in the European Union is an integral and important part of decision-making in the EU. From year to year lobbying regulation in the EU is constantly improving and the number of lobbyists increases.[41] This increase in lobbying activity is a result of the growing recognition of lobbying as a critical discipline at the intersection of politics, economics, and society.[42]

In 2003 there were around 15,000 lobbyists (consultants, lawyers, associations, corporations, NGOs etc.) in Brussels seeking to influence the EU's legislation. Some 2,600 special interest groups had a permanent office in Brussels. Their distribution was roughly as follows: European trade federations (32%), consultants (20%), companies (13%), NGOs (11%), national associations (10%), regional representations (6%), international organizations (5%) and think tanks (1%), (Lehmann, 2003, pp iii).[43][44]

In addition to this, lobby organisations sometimes hire former EU employees (a phenomenon known as the revolving door) who possess inside knowledge of the EU institutions and policy process. This practice of hiring former EU employees is part of what lobbyist Andreas Geiger describes as lobbying's vital role in shaping law and decision-making processes, given the unique insights and access these individuals provide.[42][45] A report by Transparency International EU published in January 2017 analysed the career paths of former EU officials and found that 30% of Members of the European Parliament who left politics went to work for organisations on the EU lobby register after their mandate and approximately one third of Commissioners serving under Barroso took jobs in the private sector after their mandate, including for Uber, ArcelorMittal, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America Merrill Lynch. These potential conflicts of interest could be avoided if a stronger ethics framework were established at the EU level, including an independent ethics body and longer cooling-off periods for MEPs.[45]

In the wake of the Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal in Washington, D.C., and the massive impact this had on the lobbying scene in the United States, the rules for lobbying in the EU—which until now consisted of only a non-binding code of conduct—may also be tightened.[46]

Eventually, on 31 January 2019 the European Parliament adopted binding rules on lobby transparency. Amending its Rules of Procedure, the Parliament stipulated that MEPs involved in drafting and negotiating legislation must publish online their meetings with lobbyists.[47] The amendment says that "rapporteurs, shadow rapporteurs or committee chairs shall, for each report, publish online all scheduled meetings with interest representatives falling under the scope of the Transparency Register"-database of the EU.[48]

The European allies were being lobbied by the UAE and Saudi Arabia to regain the diplomatic ties with the Syrian government. The two Arab countries lobbied the European Union for months, pushing them to ease the sanctions on Syria for the revival of its collapsed economy. The UAE and its neighbour country argued that without the ease of sanctions, the diplomatic efforts to end the Syrian war will be ineffective. However, the EU nations, including France and Germany, turned down the idea of restoring ties with Syria, stating that it would legitimize the regime that is accused of massacring its own people.[49]

France

[edit]There is currently no regulation at all for lobbying activities in France. There is no regulated access to the French institutions and no register specific to France, but there is one for the European Union[50] where French lobbyists are able to register themselves.[51] For example, the internal rule of the National Assembly (art. 23 and 79) forbids members of Parliament to be linked with a particular interest[definition needed]. Also, there is no rule at all for consultation of interest groups by the Parliament and the Government. Nevertheless, a recent parliamentary initiative[which?] (motion for a resolution) has been launched by several MPs[who?] so as to establish a register for representatives of interest groups and lobbyists who intend to lobby the MPs.[52]

Germany

[edit]In Germany, lobbying has existed since 1956, when the Federal Constitutional Court issued a ruling legalizing it. A mandatory lobby register (German: Lobbyliste) was introduced in Germany effective 1 January 2022, along with a code of conduct.[53][54] These rules were criticized as insufficient by several opposition party members and representatives from the Council of Europe, who argued that they did not adequately address issues of transparency and potential conflicts of interest.[55] Stricter rules are scheduled to come into effect on January 1, 2024.[56]

Italy

[edit]Italy does not have a lobbying legislation at national level nowadays, even though there have been proposals by lawmakers during the years. In 2016, the Chamber of deputies added an addendum that introduced a Regulation of interest representation. The Regulation expired in late 2017, when the term of the sitting Parliament expired. With the rising of the new parliamentary term in 2018, the Regulation was not being readopted.[57] At the subnational level, only six regions have legislations about lobbying: Tuscany (2002), Molise (2004), Abruzzo (2010), Calabria (2016), Lombardy (2016) and Puglia (2017). These regional legislations have similar structure, but only Tuscany took a step forward to implement this legislation and create a public register.[57]

In Italy, over the years, lobbies and power groups have obstructed the liberalization of markets and favored the protection of existing privileges. Despite various attempts to promote competition, such as the Law for the Market and Competition passed a year ago, the process has been riddled with delays, amendments and compromises that have weakened the law. Pressure from various lobbies led to the deletion of several important provisions. For example, due to pressure from pharmacists, the sale of Band C drugs in supermarkets and parapharmacies was skipped. Other provisions removed include the portability of pension funds, the sale of boxes or garages worth less than one hundred thousand euros without a notarized deed, the protected energy market, and the Postal Service monopoly. In addition, the rule on RCA tariffs was withdrawn after protests from insurance companies, while the diatribe between taxi drivers and Uber was postponed for a separate measure. Professional associations, such as lawyers and dentists, opposed measures that undermined their interests, such as the requirement for lawyers to have a quote or the requirement that dental companies be at least two-thirds owned by registered members. Other categories, such as hoteliers, called for a ban on Airbnb in the country. The lack of competitive markets is one of the main reasons Italy has not experienced economic growth in recent years. However, pressure groups continue to defend their privileges, hindering economic liberalization. The International Monetary Fund study indicates that true liberalization could grow Italy's GDP in a few years, but lobbies seem to be able to prevent such changes.[58]

A 2016 study found evidence of significant indirect lobbying of then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi through business proxies.[59] The authors document a significant pro-Mediaset (the mass media company founded and controlled by Berlusconi) bias in the allocation of advertising spending during Berlusconi's political tenure, in particular for companies operating in more regulated sectors.[59] Using advertising data from the Nielsen AdEx database, the behavior of companies buying advertising space on Mediaset television channels during Berlusconi's tenure as prime minister was analyzed. It is hypothesized that some companies are more likely to advertise on Mediaset channels when Berlusconi is in power, indicating a potential correlation between advertising behavior and political influence.

A model of the Italian television advertising market was developed, distinguishing between regulated firms (interested in government actions) and unregulated firms (less interested in specific public policy changes). The model predicts that advertising prices on Mediaset increase when Berlusconi is in power and that the mix of advertisers on Mediaset channels shifts toward regulated firms during his tenure. To assess the impact of Berlusconi's political influence, industries were ranked according to their regulatory score, obtained from a survey of Italian economists. Highly regulated industries, such as telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, and manufacturing, showed a greater tendency to allocate a portion of their advertising budgets to Mediaset during Berlusconi's tenure. Despite higher prices for advertising space on Mediaset channels during Berlusconi's tenure, companies continued to advertise, suggesting that they expect significant political benefits from supporting the network. Mediaset's advertising partners are estimated to have paid about 1.9 billion euros more during Berlusconi's three terms, indicating the expected political value of their indirect lobbying efforts. This study provides evidence of market-based lobbying, in which companies strategically allocate their advertising budgets to gain political influence. It also highlights the additional conflict of interest that politicians with corporate holdings face and raises important questions about the role of money in politics beyond direct campaign contributions.[60]

Another relevant case of lobbying that has been going on for at least 16 years concerns owners of beach establishments. Beaches are the Italian State's properties: since 2022, owners have to pay a fee of 2698 euros to keep a public concession of a beach establishment. This is an amount of money that would be paid back just by renting for three months 2 beach umbrellas for 15 euros each (and in many cases the renting prices are higher). The Court of Accounts has declared an imbalance between the fee and the gains from the beach establishment.[61] Until 2009, according to a 1949 law, people who had public concessions had the right to keep them if there was no opposition from third parties. In 2009 this law is abolished under menace of legal procedure from the Eu for infraction of a 2006 directive, that established mandatory public procedures that were impartial and transparent. Anyhow, since then, governments continuously postponed any decision regarding modifying laws on public concessions for beach establishments. Under the government of Mario Draghi the deadline for all concessions was established for 31 December 2023: anyhow, the new Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni assured in a letter of November 3, 2022, that "their government would defend the families that work in that sector",[62] and delayed the deadline of the concessions. Some politicians claim that the families involved in the issue represent a significant and influential number of electors. [63]

Finally, lobbying from taxi drivers represents a growing issue. The current situation in Italy regarding taxi services is regulated by Law No. 21 of 1992. According to this law, the responsibility for determining the number of taxi licenses, shifts, and fares is given to the municipalities. Taxi licenses are held by artisan business owners who have passed a driver's exam and are registered with the Chamber of Commerce. After holding a license for five years, reaching the age of 60, or due to illness, license holders can transfer their license to someone else upon indicating their preference to the municipality. In case of death, the license can be passed to one of the heirs or their designated individuals. Italy has an average of one taxi for every 2,000 inhabitants, whereas countries like France and Spain have ratios of 1,160 and 1,028 taxis per 2,000 inhabitants, respectively. This suggests that Italy has a relatively lower number of taxis available compared to its population. In August 2019, the then Transport Councillor Marco Granelli acknowledged the need to increase the number of taxi licenses by 450 to meet the demand. Data showed that a significant percentage of calls for taxis were going unanswered during peak hours and weekends. However, the issue was put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it remains uncertain when it will be addressed.[63]

Romania

[edit]Romanian legislation does not include an express regulation on lobbying activity. The legislative proposals initiated by various parliamentarians have not been finalized.

Attempts to regulate lobbying in Romania have appeared in the context of the fight against corruption. Anti-corruption strategies adopted in 2011 and 2004 mentions the purposes of the elaboration of a draft law on lobbying, as well as ensuring transparency in the decision-making activity.

In 2008 and 2011, the emphasis was mainly on transparency in the decision-making activity of the public authorities, regulation of lobbying activities no longer appearing as a distinct or expressly mentioned objective.[64]

The Romanian Lobby Registry Association (ARRL) was founded in June 2010 to popularize and promote lobbying activity. ARRL is a non-profit legal entity that works under private law.[65]

The majority of lobbying companies represent non-governmental organizations which activities include education, ecology, fundamental freedoms, health, consumer rights etc. Other entities that deal with lobby practice are multinational companies, Romanian companies, law firms and specialized lobby firms.

India

[edit]In India, where there is no law regulating the process, lobbying has traditionally been a tool for industry bodies like the National Association of Software and Service Companies, the Confederation of Indian Industry, the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry,[66] the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India[67][68] and other pressure groups to engage with the government ahead of the national budget and legislation in parliament. Lobbying activities have frequently been identified in the context of corruption cases, for example the 2010 controversy surrounding leaked audio transcripts of conversations between the corporate lobbyist Niira Radia and senior journalists and politicians.[69] Besides private companies, the Indian government has been paying for the services a US firm since 2005 to lobby, for example, in relation to the India-US civilian nuclear deal.[70] In India, there are no laws that defined the scope of lobbying, who could undertake it, or the extent of disclosure necessary. Companies are not mandated to disclose their activities and lobbyists are neither authorized nor encouraged to reveal the names of clients or public officials they have contacted.[71] The distinction between lobbying and bribery still remains unclear.

In 2012, Walmart revealed it had spent $25 million since 2008 on lobbying to "enhance market access for investment in India". This disclosure came weeks after the Indian government made a controversial decision to permit foreign direct investment in the country's multi-brand retail sector.[72]

Successful grassroots lobbying campaigns include the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan's campaign to pass the 2005 Right to Information Act[73] and Anna Hazare's anti-corruption campaign to introduce the 2011 Lokpal Bill.[74]

New Zealand

[edit]There is no register for lobbying activity and no cooling off period for public officials before they can enter the lobbying industry in New Zealand, allowing politicians and Parliamentary staffers to immediately become lobbyists after leaving office. Kris Faafoi joined a lobbying firm just three months after leaving Parliament, where he had been justice and broadcasting minister. Lobbyists also move directly into staffer positions. Gordon-Jon Thompson took a leave of absence from his lobbying firm to work as chief of staff to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern for four months before returning to his lobbying firm. Andrew Kirton resigned from his lobbying company on 31 January 2023 and the next day was announced as chief of staff for Prime Minister Chris Hipkins.[75]

Some ad hoc provisions against revolving door politics exist in relation to certain industries. The Immigration Advisers Licensing Act 2007, for example, prohibits Ministers of Immigration, Associate Ministers of Immigration and immigration officials from becoming a licensed immigration adviser for one year after leaving government employment.[76]

Transparency International (TI) criticized the lack of oversight in the New Zealand lobbying industry in a November 2022 report as lax.[77]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the UK, lobbying plays a significant role in the formation of legislation. Various commercial organisations, lobby groups "lobby" for particular policies and decisions by Parliament and other political organs at national, regional and local levels. The phrase "lobbying" comes from the gathering of Members of Parliament and peers in the hallways (or lobbies) of Houses of Parliament before and after parliamentary debates.[78] The now-defunct UK Public Affairs Council (UKPAC) defined lobbying as:[79] in a professional capacity, attempting to influence, or advising those who wish to influence, the UK Government, Parliament, the devolved legislatures or administrations, regional or local government or other public bodies on any matter within their competence. Formal procedures enable individual members of the public to lobby their Member of Parliament but most lobbying activity centres on corporate, charity and trade association lobbying, where organisations seek to amend government policy through advocacy.

United States

[edit]

In the United States, some special interests hire professional advocates to argue for specific legislation in decision-making bodies, such as Congress. Some lobbyists are now using social media to reduce the cost of traditional campaigns, and to more precisely target public officials with political messages.[80]

A 2011 study of the 50 firms that spent the most on lobbying relative to their assets compared their financial performance against that of the S&P 500, and concluded that spending on lobbying was a "spectacular investment" yielding "blistering" returns comparable to a high-flying hedge fund, even despite the financial downturn.[81] A 2011 meta-analysis of previous research findings found a positive correlation between corporate political activity and firm performance.[82] A 2009 study found that lobbying brought a return on investment of as much as 22,000% in some cases.[83] Major American corporations spent $345 million lobbying for just three pro-immigration bills between 2006 and 2008.[84] A review of 30 food and beverage companies spent $38.2 million on lobbying in 2020 to strengthen and maintain their influence in Washington, D.C.[85]

A study from the Kellogg School of Management found that political donations by corporations do not increase shareholder value. The authors posit a few reasons that firms continue giving despite little returns, including signaling firm values to investors and consumption value for individual managers.[86][87]

Wall Street spent a record $2 billion trying to influence the 2016 United States presidential election.[88][89]

Foreign lobbying

[edit]

Foreign-funded lobbying efforts include those of Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, and China lobbies. In 2010 alone, foreign governments spent approximately $460 million on lobbying members of Congress and government officials.[90]

In the US, lobbying for foreign governments is not illegal, but it requires registering as a foreign agent with the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).[91][92] Unofficially, according to Politico, 'many lobbyists try to avoid representing countries that have tense relationships with Washington or troubled human rights records'. Between 2015 and 2017, around 145 registered lobbyists were paid $18 million by Saudi Arabia to influence the U.S. government.[93]

In January 2017, an order by Donald Trump led to a lifetime ban on administration officials from lobbying for foreign governments and a five-year ban on other forms of lobbying.[94] However, the rule was revoked by Trump right before the end of his presidency.[95] A number of Trump allies were found guilty to lobbying on behalf of foreign governments during the 2016 US elections, including Paul Manafort and Elliott Broidy.[91]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]The United Arab Emirates has a long history of lobbying government and politicians in the West for its conflict of interest concerning building influence and using it to impact the country's foreign policy.[96][97] In November 2022 it was accused of hiring PR and lobbying firms in order to promote to the politicians in the United States about its selection to host the COP28 Climate Conference. The problem was that the promotion started even before Egypt hosted 2022's COP27 Climate event. Fleishmann Hillard were hired to compose letters that proposed the idea of Emirati ministers attending conferences and events and using the phrase "the UAE is hosting COP28 next year". Whereas, Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld were hired to reach out to US politicians particularly pushing the environmental policies or favouring fossil fuels in addition to informing them about the UAE hosting COP28. The gulf nation even declared its intentions of achieving net zero emissions by 2050, even though 30% of their GDP relies on oil and gas directly, while the remaining relies upon industry run on heavy energy consumption.[98]

In February 2024, New Westminster Mayor Patrick Johnstone faced scrutiny after attending the COP28 conference. Johnstone’s expenses, including the conference fees, travel and accommodation, were incurred by C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, of which Dubai is a member of sterling committee. Councillors Daniel Fontaine and Paul Minhas filed a complaint against Johnstone for breaking the state’s code of conduct. The investigation was assigned to Commissioner Jennifer Devins, who, in her October 2024 report, stated that Johnstone’s trip provided personal benefits, which councillors are restricted from accepting. While Devins did not impose sanctions, she recommended Johnstone to take training on the laws of country.[99][100][101]

A firm based in UAE, Alasriya Media Consultancy paid $10,000 a former CIA analyst Larry Johnson to run his podcast Counter Currents. The podcast discusses global politics, including pro-Russian narrative of the Ukraine war and US foreign policy in the Middle East. The contract was signed in May 2024, but wasn’t disclosed in FARA filing until November. The Emirati firm is represented by a Lebanese celebrity journalist, Ghina Amyouni, whose reason to fund the podcast was unclear.[102]

Other

[edit]- Israel (1994)[103] – a unique lobby which is called "Lobby 99" is working at the Israeli parliament. This is a lobby which is funded by the people by crowdfunding and working for the people, the 99 percent who are not among the elites which most lobbying companies represent.

- Ukraine: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has signed into law the much-anticipated legislation on lobbying, officially known as draft law No. 10337[104]

- Kazakhstan: Since 1998, Kazakhstan has been trying to pass a law on lobbying.[105] The National Chamber of Entrepreneurs of Kazakhstan "Atameken" is one of the first official lobbying structures in the country, but there are other examples.[106]

- South Korea: In South Korea, lobbying is viewed as a form of corruption and is illegal.[107]

- United Nations are relevant to NGO lobbying.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Lobbying Versus Advocacy: Legal Definitions". NP Action. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Arab Lobby in the United States Handbook, 2015 edition, published by the Global Investment Center, United States (ISBN 1-4387-0226-4)

- ^ Karr, Karolina (2007). Democracy and lobbying in the European Union. Campus Verlag. p. 10. ISBN 9783593384122.

- ^ Balles, Patrick; Matter, Ulrich; Stutzer, Alois (31 May 2024). "Special Interest Groups Versus Voters and the Political Economics of Attention". The Economic Journal. 134 (662): 2290–2320. doi:10.1093/ej/ueae020. hdl:10419/193239. ISSN 0013-0133.

- ^ Higashi, Alejandro (2012-07-01). "Lexicon Latinitatis Medii Aevi Regni Legionis (s. VIII-1230) Imperfectum/Léxico latinorromance del reino de León (s. VIII-1230).Editioni curandae prefuit Maurilio Pérez. Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, 2010 (Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis)". Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica. 60 (2): 582. doi:10.24201/nrfh.v60i2.1062. ISSN 2448-6558.

- ^ "BBC Definition of lobbying". BBC News. 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ a b "A Lobbyist by Any Other Name?". NPR. January 22, 2006.

- ^ Deanna Gelak (previous president of the American League of Lobbyists) mentioned this in her book Lobbying and Advocacy: Winning Strategies, Resources, Recommendations, Ethics and Ongoing Compliance for Lobbyists and Washington Advocates, TheCapitol.Net, 2008, LobbyingAndAdvocacy.com

- ^ "NP Action - Lobbying Versus Advocacy: Legal Definitions". Archived from the original on 2010-04-02.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Definitions".

- ^ "EU lobbyists face tougher regulation | Financial Times".

- ^ A. Paul Pross. "Lobbying – The Canadian Encyclopedia". Encyclopediecanadienne.ca. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ NAACP; People, National Association for the Advancement of Colored (2009-02-21). "The Civil Rights Era - NAACP: A Century in the Fight for Freedom | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ "amicus curiae". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ Blanes i Vidal, Jordi; Draca, Mirko; Fons-Rosen, Christian (2012-12-01). "Revolving Door Lobbyists". American Economic Review. 102 (7): 3731–3748. doi:10.1257/aer.102.7.3731. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Lapira, Timothy; Thomas, Herschel (2017). Revolving Door Lobbying: Public Service, Private Influence, and the Unequal Representation of Interests. University Press of Kansas. doi:10.1353/book52376. ISBN 978-0-7006-2451-5. S2CID 259463846.

- ^ Gangitano, Alex (2019-02-12). "Ex-lawmakers face new scrutiny over lobbying". The Hill. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ Burger, Timothy J. (2006-02-16). "The Lobbying Game: Why the Revolving Door Won't Close". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ^ "Revolving Door: Methodology". Opensecrets.org. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25.

- ^ Nesterovych, Volodyymyr (2016). "International standards for the regulation of lobbying (EU, CE, OECD, CIS)". Krytyka Prawa. tom 8, nr 2: 79–101 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Margaret Chan (10 June 2013). "Opening address at the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion". www.who.int. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019..

- ^ a b Dellmuth, Lisa Maria; Tallberg, Jonas (2017). "Advocacy Strategies in Global Governance: Inside versus Outside Lobbying". Political Studies. 65 (3): 705–723. doi:10.1177/0032321716684356. ISSN 0032-3217.

- ^

For example:

Nicholls, Andrew D. (1999). "Kings, Courtiers, and Councillors: The Making of British Policy". The Jacobean Union: A Reconsideration of British Civil Policies Under the Early Stuarts. Contributions to the study of world history, ISSN 0885-9159. Vol. 64. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group R. D. p. 51. ISBN 9780313308352. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

The royal court was home to the king and therefore was an important arena for policy issues and decisions. [...] we find isolated examples of lobbyists for particular interests. An example of such a figure was Sir John Hay, who spent frequent intervals at court during [the reigns of James VI/I and Charles I] when he acted as agent for the Scottish Royal Burghs.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Julian (2006). Lobbying In Australia: You Can't Expect Anything to Change If You Don't Speak Up.

- ^ a b Warhurst, John (2013-03-13). "Shopping for influence". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ a b c d Grattan, Michelle (10 April 2013). "Liberal lobbyists look to the good times". The Conversation. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ "Who is on the register?". Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 2018-12-01. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ "About the Register". Public Sector Commission – Register of Lobbyists. Government of Western Australia. 2011-07-20. Archived from the original on 2015-02-28. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ "Register of Lobbyists : Register of Lobbyists". lobbyists.dpac.tas.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2015-07-03.

- ^ "South Australian Lobbyist Code of Conduct and Public Register". Department of Premier & Cabinet. Government of South Australia. Archived from the original on 2015-04-11. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ "Questions and answers for Victorian Register of Lobbyists". Victorian Public Sector Commissioner – Register of Lobbyists. State Government of Victoria. 2014-06-20.

- ^ Smith, Matt (2016-10-22). "Who plays the lobby game in Tasmania". Mercury. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ^ Doward, Jamie; Latimer, Charlotte (2013-11-24). "Plush hotels and caviar diplomacy: how Azerbaijan's elite wooed MPs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ Caviar Diplomacy. How Azerbaijan silenced the Council of Europe Archived 2017-09-11 at the Wayback Machine // ESI, 24 May 2012

- ^ «Икорная дипломатия» Баку в сфере прав человека Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine // RFE/RL, 12.11.2013

- ^ Council of Europe plagued by 'caviar diplomacy' Archived 2017-07-30 at the Wayback Machine // EURACTIV 23 03 2017

- ^ Will IOG go for Baku's 'caviar diplomacy' ? Archived 2017-08-07 at the Wayback Machine // Africa Intelligence, 9 02 2017 г. "Baku's "caviar diplomacy" which consisted of buying the good graces of certain members of the Council of Europe"

- ^ Rankin, Jennifer (14 December 2022). "Revealed: MEP in prisoner resolution row made undeclared Bahrain visit". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions". Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. October 10, 2014. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ Sapers, J. in Ferguson, G. (2018). Chapter 10: Regulation of Lobbying. Global Corruption: Law, Theory and Practice. 3rd Edition. University of Victoria Press. https://www.canlii.org/en/commentary/doc/2018CanLIIDocs28#!fragment//BQCwhgziBcwMYgK4DsDWszIQewE4BUBTADwBdoByCgSgBpltTCIBFRQ3AT0otokLC4EbDtyp8BQkAGU8pAELcASgFEAMioBqAQQByAYRW1SYAEbRS2ONWpA

- ^ Nesterovych, Volodymyr (2015). "EU standards for the regulation of lobbying". Prawa Człowieka. 18: 98, 106.

- ^ a b Geiger, Andreas (2012). EU lobbying handbook (2. ed.). Brussels: Helios Media. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-1-4751-1749-3.

- ^ Lehman, Wilhelm (2003). "Lobbying in the European Union: current rules and practices" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-11-17. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ Petrillo, Pier Luigi (21 February 2013). "Form of government and lobbying UK and UE, a comparative perspective". Apertacontrada. Archived from the original on Oct 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Transparency International EU (2017) Access All Areas: when EU politicians become lobbyists". 31 January 2017.

- ^ Green Paper on European Transparency Initiative European Commission, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2009

- ^ "EU Parliament to end secret lobby meetings". 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Text adopted by EU Parliament on lobbying transparency" (PDF).

- ^ Adghirni, Samy (2023-06-15). "Saudis, UAE Lobby Europeans to Restore Ties With Syria's Assad". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ "Pleins feux sur les lobbies dans l'UE (28 October 2009)". Ec.europa.eu. 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ Pseudo *. "Le lobbying passe aussi par le web (12 March 2012)". Dsmw.org. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ "French National Assembly : Motion for a Resolution on Lobbying (21 November 2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009.

- ^ als/dpa (16 June 2021). "Kabinett beschließt Verhaltenskodex für Lobbyisten". Spiegel. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ AFP, dpa, tst (10 May 2021). "Europarat bemängelt Deutschlands Kampf gegen Korruption". Die Zeit. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "ZEIT ONLINE | Lesen Sie zeit.de mit Werbung oder im PUR-Abo. Sie haben die Wahl". www.zeit.de. Archived from the original on 2023-07-25. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ^ Müller, Volker. "Deutscher Bundestag - Vorlagen zur Änderung des Lobbyregistergesetzes überwiesen". Deutscher Bundestag (in German). Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ^ a b "At a glance: Government lobbying in Italy". 7 April 2021.

- ^ "In Italia le lobby fanno fallire la legge sulla concorrenza". 9 March 2016.

- ^ a b DellaVigna, Stefano; Durante, Ruben; Knight, Brian; Ferrara, Eliana La (2016). "Market-Based Lobbying: Evidence from Advertising Spending in Italy †". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 8 (1): 224–256. doi:10.1257/app.20150042.

- ^ "American Economic Association". www.aeaweb.org.

- ^ Consiglio dei Ministri. (3 November 2022). Letter from Giorgia Meloni to President Capacchione, Il Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri. https://ww.mef.gov.it/inevidenza/documenti/NADEF_2018.pdf

- ^ "Gentile Presidente Capacchione" (PDF). www.mondobalneare.com. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Balneari e taxi, come funziona l'Italia delle lobby | Milena Gabanelli". 14 November 2022.

- ^ Lobby în Romania vs. Lobby în UE (in Romanian). Bucharest: Institutul European din România. 2015. p. 67. ISBN 978-606-8202-46-4.

- ^ "Asociatia Registrul Român de Lobby – Bun venit pe pagina Asociaţiei Registrul Român de Lobby!". registruldelobby.ro. Retrieved 2021-11-05.

- ^ Goyal, Malini; Sharma, Shantanu N (2012-06-03). "Why India Inc's lobby groups like CII, Ficci & Nasscom have lost sheen". The Economic Times.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India - TobaccoTactics". tobaccotactics.org. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ Mishra, Asit Ranjan (2021-06-02). "Assocham seeks wage support for MSMEs". mint. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ Kumar, Akanksha (2018-02-02). "Radia Tapes: How One Woman's Influence Peddling Led to a Snake Pit". TheQuint. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ "Indian government cuts down on US lobbying to lowest in 7 years". The Economic Times. July 30, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ Kalra, Kaushiki Sanyal, Harsimran (2013-06-19). "A case for lobbying in India". mint. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Wal-Mart Lobbying in India? - Case - Faculty & Research - Harvard Business School". www.hbs.edu.

- ^ "20 Years of the Right to Information Movement". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ^ "Govt issues notification on committee to draft Lokpal Bill". The Hindu. New Delhi. Press Trust of India. 9 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Espiner, Guyon (25 March 2023). "Lobbyists in New Zealand enjoy freedoms unlike most other nations in the developed world". RadioNewZealand. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ "New Zealand Legislation". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- ^ "New Zealand lobbying oversight lacking in comparison to similar countries". Transparency.org. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- ^ "Lobbying". BBC. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Lobbying Definition". UK Public Affairs Council. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Government Lobbyists Are More Nimble Than Ever". Fortune. 13 June 2016.

- ^ Brad Plumer (October 10, 2011). "The outsized returns from lobbying". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

...Hiring a top-flight lobbyist looks like a spectacular investment ...

- ^ Lux, Sean; Crook, T. Russell; Woehr, David J. (January 2011). "Mixing Business With Politics: A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Outcomes of Corporate Political Activity". Journal of Management. 37 (1): 223–247. doi:10.1177/0149206310392233. S2CID 144560276. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Alexander, Raquel Meyer; Mazza, Stephen W.; Scholz, Susan (2009). "Measuring Rates of Return for Lobbying Expenditures: An Empirical Case Study of Tax Breaks for Multinational Corporations". Journal of Law and Politics. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1375082. hdl:1808/11410. S2CID 167518602. SSRN 1375082.

- ^ "How did opening borders to mass immigration become a 'Left-wing' idea?". 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Doering, Christopher. "Where the dollars go: Lobbying a big business for large food and beverage CPGs". fooddive.com. Food Dive.

- ^ "When Corporations Donate to Candidates, Are They Buying Influence?". 5 September 2017.

- ^ Fowler, Anthony; Garro, Haritz; Spenkuch, Jörg L. (2020). "Quid Pro Quo? Corporate Returns to Campaign Contributions". The Journal of Politics. 82 (3): 844–858. doi:10.1086/707307. ISSN 0022-3816. S2CID 11322616.

- ^ "Wall Street spends record $2bn on US election lobbying". Financial Times. March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Wall Street Spent $2 Billion Trying to Influence the 2016 Election". Fortune. March 8, 2017.

- ^ Knott, Alex (September 14, 2011). "Lobbying by Foreign Countries Decreases". Roll Call. Archived from the original on Aug 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Meyer, Theodoric (24 January 2021). "One of Trump's final acts will allow former aides to profit from foreign ties". Politico. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Philip (July 21, 2021). "Foreign Lobbying Isn't Inherently Bad—Until There Are Lies". TIME. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Fang, Lee (2017-05-19). "As Trump Travels to Saudi Arabia, the Kingdom's D.C. Lobbying Surge Is Paying Off". The Intercept. Archived from the original on Feb 6, 2024.

- ^ "Trump imposes lifetime ban on some lobbying, five years for others". CNBC. 29 January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ "Trump revokes rule barring lobbying by former officials as he leaves office". CNN. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "The Emirati Lobby: How the UAE Wins in Washington" (PDF). Center for International Policy. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ "Trump Ally's UAE Lobbying Struck Heart of Democracy, U.S. Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "UAE using role as Cop28 host to lobby on its climate reputation". The Guardian. 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Chan, Cheryl (1 November 2024). "New West mayor's all-expenses paid trip to Dubai breached ethics rules: Commissioner". Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Dubai, United Arab Emirates". C40 Cities. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Pawson, Chad (31 October 2024). "New West mayor accepts ethics commissioner's recommendation for training on receiving gifts". Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Former CIA officer launches political podcast funded by UAE firm linked to Lebanese journalist". The Wall Street Journal. 11 December 2024.

- ^ "Lobbies in the Knesset". Knesset.gov.il. 1997-04-01. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ Cheplyk, Roman (2024-03-12). "President Zelensky Signs Law on Regulated Lobbying". GTInvest Ukraine. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ Трубачева, Татьяна (2 May 2018). "Нужно ли в Казахстане узаконить лоббистов?". Forbes Kazakhstan. Archived from the original on Oct 12, 2023.

- ^ "Lobbying interests in the structures of Kazakhstan". Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- ^ "In Korea, lobbying takes different forms". Korea JoongAng Daily. 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

Bibliography

[edit]- Zelizer, Julian E., ed. The American Congress: The Building of Democracy (Houghton Mifflin. 2004) passim.

- Joos, Klemens: Convincing Political Stakeholders – Successful Lobbying Through Process Competence in the Complex Decision-Making System of the European Union, 526 pages, ISBN 978-3-527-50865-5, Wiley VCH 2016

- Petrillo, P. L. (21 February 2013). "Form of government and lobbies in UK and UE. A comparative perspective". Apertacontrada.

- Joos, Klemens: Lobbying in the new Europe. Successful representation of interests after the Treaty of Lisbon, 244 pages, ISBN 978-3-527-50597-5, Wiley VCH 2011

- Nesterovych V. (2015) EU standards for the regulation of lobbying. Prawa Człowieka. nr 18: 97–108.

- Nesterovych, Volodymyr (2010). "Legalization, accreditation, control and supervisory activity concerning lobbyists and lobbying organizations: prospects for Ukraine Archived 2020-08-03 at the Wayback Machine". Power. Man. Law. International Scientific Journal. No. 1: 96–105.

- Geiger, Andreas: EU Lobbying handbook, A guide to modern participation in Brussels, 244 pages, ISBN 3-9811316-0-6, Helios Media GmbH, 2006

- GLOSSARY – Alphabetical list of terms associated with the Lobbying industry

- The Bulletin, 16 March 2006, p. 14, Lobbying Europe: facts and fiction

- The European Lawyer, December 2005/January 2006, p. 9, The lobbyists have landed

- Financial Times, 3 October 2005, p. 8, Brussels braces for a U.S. lobbying invasion

- Public Affairs News, November 2004, p. 34, Judgement Call

- The European Lawyer, December 2004/January 2005, p. 26, Lifting the lid on lobbying

- Pier Luigi Petrillo, Democracies under Pressures. Lobbies and Parliaments in a comparative public law, Giuffrè 2011 (www.giuffre.it)

- Pietro Semeraro, I delitti di millantato credito e traffico di influenza, ed. Giuffre, Milano, 2000.

- Pietro Semeraro, Trading in Influence and Lobbying in the Spanish Criminal Code, PDF

- Wiszowaty, Marcin: Legal Regulation of Lobbying in New Members States of the European Union, Arbeitspapiere und Materialien – Forschungsstelle Osteuropa an der Universitat Bremen, No. 74: Heiko Pleines (ed.): Participation of Civil Society in New Modes of Governance. The Case of the New Member States. Part 2: Questions of Accountability. February 2006 (PDF)

- Heiko Kretschmer/ Hans-Jörg Schmedes: Enhancing Transparency in EU Lobbying? How the European Commission's Lack of Courage and Determination Impedes Substantial Progress, Internationale Politik und Gesellschaft Archived 2021-03-14 at the Wayback Machine 1/ 2010, S. 112–122

- "Lobbying". BBC News: Politics. London: BBC. 22 December 2005. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- "Police loans inquiry is widenened". London: BBC News. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-30.